I'm coming a little late to this text, but I found it to be a fascinating read. Originally published in 1985 in Socialist Review, "A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century" initially sprang from a debate in feminist studies, but it quickly became the catalyst—at least in the humanities—for a new way of thinking about how the individual and society interact with machines. Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Nick Montfort write in their introduction to the essay in The New Media Reader (n.b. page references below are from this version of the text),"Haraway's cyborg preference has led some readers into uninteresting interpretations, in which it is assumed that Haraway's project is an attack on radical feminists such as Mary Daly" (515). I'm not so sure that such interpretations would be "uninteresting" to feminist studies scholars, but their larger point—that the influence of Haraway's essay has outgrown it's feminist roots "and may indeed be the starting point for current progressive scholarship on science and technology" (515)—is well taken.

I'm coming a little late to this text, but I found it to be a fascinating read. Originally published in 1985 in Socialist Review, "A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century" initially sprang from a debate in feminist studies, but it quickly became the catalyst—at least in the humanities—for a new way of thinking about how the individual and society interact with machines. Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Nick Montfort write in their introduction to the essay in The New Media Reader (n.b. page references below are from this version of the text),"Haraway's cyborg preference has led some readers into uninteresting interpretations, in which it is assumed that Haraway's project is an attack on radical feminists such as Mary Daly" (515). I'm not so sure that such interpretations would be "uninteresting" to feminist studies scholars, but their larger point—that the influence of Haraway's essay has outgrown it's feminist roots "and may indeed be the starting point for current progressive scholarship on science and technology" (515)—is well taken.

In the essay, Haraway argues that the focus on dualisms—between "mind and body, animal and machine, idealism and materialism" (519)—as the basis for progressive resistance to injustice was no longer useful. According to Haraway, "a slightly perverse shift of perspective might better enable us to contest for meanings, as well as for other forms of power and pleasure in technologically mediated societies" (519). That shift was to establish the cyborg as a mythos for this resistance. In the remainder of the essay, Haraway argues that since the "cyborg world" was free of these dualisms, it would be open to the possibility of being "about lived social and bodily realities in which people are not afraid of their joint kinship with animals and machines, not afraid of permanently partial identities and contradictory standpoints" (519).

What was most interesting to me about the essay was that Haraway defined the cyborg as not merely the combination of human and machine, although this is the most common popular use of the term. Instead, she claims that

a cyborg is a cybernetic organism, a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction. (516)

While Haraway frequently refers to the combination of person and machine as defining the mythology of the cyborg, the crucial move she makes in the essay is to demonstrate how the processes of language have already made the cyborg a social reality. Of course, she writes, "modern medicine is…full of cyborgs, of couplings between organism and machine" (516), yet machines aren't only fashioned from cogs and gears, or circuits and switches. Society is a machine, as is language, and Haraway argues that social theory must take into account the degree to which our humanity is intertwined with physical and social tools, using the cyborg as the metaphor for understanding the connection.

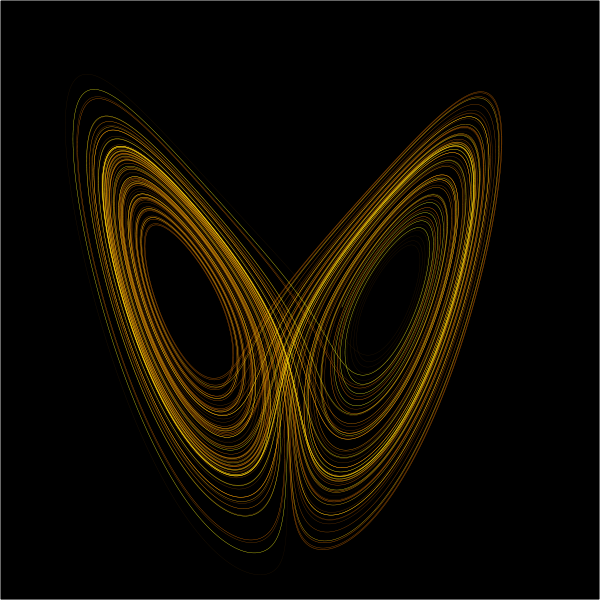

A tree visualization of Haraway's use of "cyborg" in "Cyborg Manifesto"

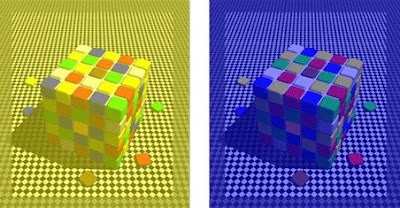

One particular way in which we can see this connection between language, machine, and body is the trend in the sciences to translate everything into readable code. Haraway notes that "biology and evolutionary theory over the last two centuries have simultaneously produced modern organisms as objects of knowledge" (517) and that the technologies of communication and biological manipulation "are the crucial tools recrafting our bodies," for "communications sciences and modern biologies are constructed by a common move—the translation of the world into a problem of coding" (524). In other words, not only are we literally colonizing our bodies with machines, we compose them as texts as well, thereby rendering them more susceptible to refashioning through language.

The Human Genome Project and self-administered DNA tests are just a few of the examples of the ways in which "reading" the code of our bodies is changing the ways in which we think about ourselves. According to Haraway, language has played a crucial role in way in which

late twentieth-century machines have made thoroughly ambiguous the difference between natural and artificial, mind and body, self-developing and externally designed, and many other distinctions that used to apply to organisms and machines (518)

while language—or "communications breakdown"—is the key to stress, the "privileged pathology" of the cyborg (524).

Haraway insists more than once that the cyborg isn't interested in history or looking backward. However, if we accept her conclusions about the role of language and other technologies in creating cyborgs, then we have to admit that we have always been cyborgs. Convincing evidence in the study of distributed cognition suggests that our cognitive functions are not contained solely in ourselves, but are rather spread throughout our environment, particularly in our tools. Language is one such tool, and Haraway's work suggests that language is always embodied. She writes that our "bodies are maps of power and identity" (534), and language has played a crucial role in the ways in which that power and identity is enacted.

At the third level, Berners-Lee points out that users began to realize that it is what the documents are about, not the documents themselves, that was important. This level is similar to the semantic web, and Berners-Lee calls it “the graph.” (Actually, he calls it the “Giant Global Graph,” riffing on the WWW.) As users are able to capitalize on the graph, he argues, they will be able to exercise more power from their computing tasks, just as the innovations of the net and the web made computing more powerful at those levels. However, to make optimal use of the graph, designers will have to allow for the information stored in their documents to be able to freely interact with the information on other pages.

At the third level, Berners-Lee points out that users began to realize that it is what the documents are about, not the documents themselves, that was important. This level is similar to the semantic web, and Berners-Lee calls it “the graph.” (Actually, he calls it the “Giant Global Graph,” riffing on the WWW.) As users are able to capitalize on the graph, he argues, they will be able to exercise more power from their computing tasks, just as the innovations of the net and the web made computing more powerful at those levels. However, to make optimal use of the graph, designers will have to allow for the information stored in their documents to be able to freely interact with the information on other pages.