I ran across Remote Relationships in a Small World a month or so ago in a publisher’s catalog, and I thought it looked pretty promising, seeing as my work is gravitating towards studies of social networks and mobile communication. The collection of essays are intended, according to editor Samantha Holland, to provide new research on social relationships conducted online. This, I assume, is the source of the title, which suggests that the digital age has both made the world smaller by allowing for instant communication across time and space, but at the same time that time and space is real and has a real effect on the relationships conducted online.

The three chapters that jumped out at me were Holland’s chapter (with Julie Harpin) on the use of MySpace by British teenagers, Janet Finlay and Lynette Willoughby’s study of the use of WebCT forums and blogs in online learning, and Simeon J. Yates and Eleanor Lockley’s study of male and female cell phone use. (The complete TOC can be found here.)

Holland and Harpin presented the results of a pilot study of teenage British MySpace users, following the usage habits of 12 teenagers. Their results seemed to confirm the work of boyd and Ellision (2007) in that the teenagers they studied tended to use MySpace to communicate with people they already knew socially. Additionally, the authors found that, unlike the typical stereotype of the digital loner, the social network was a “hive of sociability.”

Similarly, Finlay and Willoughby’s chatper didn’t break any new ground. They found that a minority of the (mostly male) students using their course forum and individual blogs would post offensive messages, and that this behavior tended to alienate other users. After their mostly textual case study, the authors concluded that for an online learning space to be a real community of practice there needed to be scaffolded interactions with the community so that users could become socialized to it, a feat which was not possible in their 12-week course.

Finally, Yates and Lockley examined the use of cell phones by men and women in a number of different contexts: at home, on the train, and in other public places like restaurants and coffee shops. They found that the men in their study tended to send shorter messages than the women, and that the longest messages were sent in conversations between two women. Like Holland and Harpin, the authors found that the participants in their study tended to not use their phones to contact or converse with strangers, but rather to keep in touch with people who were close to them, both physically (neighbors) and emotionally (friends and relatives).

I found this collection to be a bit of a mixed bag. While the studies I mentioned here were interesting, and had interesting conclusions, I found myself wishing they were a bit more rigorous. This was particularly the case with the Holland and Harpin and Finlay and Wiloughby chapters. While each was interesting, neither broke new ground, and both seemed to merely share the overall theme of the online texts they collected. Admittedly the Holland and Harpin study was a preliminary one, but, that being the case, I wonder why it was included in this collection.

The Yates and Lockley chapter suffered from the opposite problem. The authors used a large number of measures—surveys, observation, diary studies, focus groups—but the analysis and discussion of these measures seemed abrupt to me. I would have liked to have seen them choose some of the data to focus on with more depth and detail, rather than have them present this cornucopia of data.

That said, I found the book to be useful, not the least for the support, however tentative, that the studies included in it lend to the thesis that social communication is used more to keep in contact with people in existing social networks, rather than create new contacts. Somewhat ironically, these studies seem to suggest that our online relationships aren’t so “remote” after all.

Monday, March 17, 2008

Review: Holland, ed. Remote Relationships in a Small World (2007)

Posted by

John Jones

at

6:49 PM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: cellphones, CMS, Communication, enaction, Mobile phone, MySpace, Online Communities, research, Review, SMS, social networking

Monday, January 21, 2008

Facebook relies on user-generated translations

MySpace and Facebook are both trying to expand their markets outside of the English-speaking world. According to Tech Crunch, MySpace is doing this by creating local offices. However,

Facebook is taking a radically different approach—tapping users to do all the hard work for them. They are picking and choosing markets (Spanish was opened first, two weeks ago; today German and French were launched) and asking just a few users to test out their collaborative translation tool. Once the tool is perfected and enough content has been translated, Facebook will offer users the ability to quickly switch the language on the site, per their preference.

Like Google has done with image search and Wikipedia has done all along, sometimes it just makes sense to ask you users to do as much work as possible. As long as users go along with it, everyone is happy.

via Tech Crunch

Posted by

John Jones

at

8:57 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: Communication, facebook, translation

Sunday, January 20, 2008

NY Times on cellphone novels

Norimitsu Onishi of the New York Times has written an article on the popularity of cellphone novels in Japan. While the phenomenon has been around for almost a decade (Onishi dates it back to 2000), it was reported at the end of 2007 that half of Japan’s top ten novels of the year were written on cellphones. The article provides some interesting background to the phenomenon.

The cellphone novel was born in 2000 after a home-page-making Web site, Maho no i-rando, realized that many users were writing novels on their blogs; it tinkered with its software to allow users to upload works in progress and readers to comment, creating the serialized cellphone novel. But the number of users uploading novels began booming only two to three years ago, and the number of novels listed on the site reached one million last month, according to Maho no i-rando.

The boom appeared to have been fueled by a development having nothing to do with culture or novels but by cellphone companies’ decision to offer unlimited transmission of packet data, like text-messaging, as part of flat monthly rates. The largest provider, Docomo, began offering this service in mid-2004.

This kind of trend makes literary-types upset. One worry is that few of the current crop of cellphone novelists have ever written before. According to the article, cellphone authors aren’t being compelled to write for traditional literary reasons.

“It’s not that they had a desire to write and that the cellphone happened to be there,” said Chiaki Ishihara, an expert in Japanese literature at Waseda University who has studied cellphone novels. “Instead, in the course of exchanging e-mail, this tool called the cellphone instilled in them a desire to write.”

Interestingly, one author of a cellphone novel, Rin, acknowledges the literacy divide between the writers/readers of cellphone novels and other kinds of novel reading. Here she explains why the readers of her novel aren’t interested in traditional novels.

“They don’t read works by professional writers because their sentences are too difficult to understand, their expressions are intentionally wordy, and the stories are not familiar to them,” she said. “On other hand, I understand how older Japanese don’t want to recognize these as novels. The paragraphs and the sentences are too simple, the stories are too predictable. But I’d like cellphone novels to be recognized as a genre.”

Posted by

John Jones

at

6:02 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: cellphones, Communication, Emergence, literacy, micro-fiction, novels, Writing

Wednesday, December 19, 2007

Teens privacy savvy

CNET News is reporting on a Pew Internet & American Life Project study called “Teens and Social Media,” which found that teenage girls tend to blog more than teenage boys (35% and 20%, respectively) and that teenage boys post more videos online than girls (19% of boys have posted a video online compared to 10% for girls).

However, for me the most interesting news is that teens take greater measures to protect their privacy online than adults do.

But how safe are teens being in protecting their personal information and images? More safe than adults, apparently. About 66 percent of teens with a social network profile restrict access in some way and 77 percent of teens who upload photos restrict access some of the time, while only 58 percent of adults who post photos restrict access.

For video, a smaller percentage (54 percent) of teens restrict access, about the same as adults.

Posted by

John Jones

at

6:29 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: Communication, Internet, privacy, research, Writing

Wednesday, December 12, 2007

Personal publishing and micro-fiction

Cameron Reilly of The Podcast Network has created a new site, Twittories, for crowdsourced stories composed in Twitter (via TechCrunch).

My wife and I were putting our kids to bed and we were doing something we have done with them since they were about two years of age. One of us starts a new story by telling a few lines and then the next person picks up where they left off and so on. I thought “gee, this is like a Twitter conversation” and started to wonder what it would be like to have a bunch of folks on twitter collaborate on a short story—140 characters at a time.

Apparently, a similar phenomenon has already demonstrated that it has legs: in Japan, novels are currently written and consumed on cellphones.

In a related post on Read/Write Web, Alex Iskold responds to a post by Fred Wilson on microblogging (Wilson drew the graph above), expanding on Wilson’s claim that microblogging fits a niche in personal publishing not met by chat, social networking, or blogging. Iskold concludes his piece this way:

The personal publishing market evolved from cumbersome web sites to online diaries called blogs to social networks and more recently to microblogs. Each form of personal publishing is different and each has its niche and audience. While social networks have been the most wide spread, the content creation there feels different from publishing. Because traditional blogging platforms are powerful and still require technical know-how, microblogging has evolved as an intermediate form of self-publishing. Microblogging has a shot of spreading blogging further into the mainstream as well as swaying some professional bloggers to start personal blogs.

Although Iskold doesn’t mention micro-fiction like Twittories in his post, it will be interesting to see how this kind of writing fits into the microblogging niche.

Posted by

John Jones

at

1:22 PM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: cellphones, Communication, crowd-sourcing, micro-fiction, microblogging, Twitter, Writing

Saturday, November 17, 2007

Teens use IM to avoid emotional communication

According to a new poll from AOL and the AP, nearly half of teenagers use instant messaging services, compared to only about 20 percent usage by adults. Interestingly, a large chunk of those teens prefer IM for communications with heavy emotional content:

An estimated 43 percent of teens who instant message use the tool for emotionally charged conversations, according to a poll from AOL and the Associated Press that was released Thursday. Those conversations might include making and breaking dates.

The poll—which questioned 410 teens and more than 800 parents—found that 22 percent of teens use IM to ask people out on a date or accept one, and 13 percent of teens use instant chat to break up. Girls are also more likely to use IM to avoid uncomfortable talks. According to the poll, about half of girls and more than a third of boys said they’ve used instant chat to say what they wouldn’t say in person.

via: CNET News Blog

Related: “Email is dead. Long live email!”

Posted by

John Jones

at

2:00 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: Communication, enaction, IM

Thursday, November 15, 2007

Email is dead. Long live email!

So, it turns out that the youth of today no longer use email, preferring the IM and chat. Oh, wait; maybe that was the youth of five years ago. At any rate:

e-mail is looking obsolete. According to a 2005 Pew study, almost half of Web-using teenagers prefer to chat with friends via instant messaging rather than e-mail. Last year, comScore reported that teen e-mail use was down 8 percent, compared with a 6 percent increase in e-mailing for users of all ages. As mobile phones and sites like Twitter and Facebook have become more popular, those old Yahoo! and Hotmail accounts increasingly lie dormant.

However, there is some hope for email yet. Apparently Yahoo and Google are attempting to reanimate email’s rotting corpse as the backbone of their respective social networking strategies. Clearly, people still get worked up about email, but it is possible that, over time, email will morph into a primarily business communication tool, as the most formal—or, perhaps, the oldest and therefore least scary—of online communication methods.

Posted by

John Jones

at

11:40 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: Communication, email, Emergence, enaction, facebook, Google, IM, social networking, Twitter, Yahoo

Monday, October 08, 2007

Ass-mar

Apparently, doctors have a hard time treating Spanish-speaking patients with asthma because there is no word for “wheeze” in Spanish.

From The New York Times:

According to a survey conducted by asthma specialists at Columbia University Medical Center, which is situated in the heavily Dominican neighborhood of Washington Heights, there is no precise translation for the word “wheeze.”

In interviews with 39 Spanish speakers, “wheeze” was translated into 12 different Spanish expressions, including “tight chest,” “suffocation,” “asphyxiation,” “snoring” and “congested breathing.” (Nine of the respondents could not come up with any translation at all). While accredited translators came up with the term “ronquido” or “sibilancia,” only 6 of the 39 agreed with that “ronquido” and none agreed with “sibilancia” (even though that seems to be the choice of many readers here; see the comments below).

Wheezing, which according to the National Institutes of Health is a high-pitched whistling sound during breathing that often occurs when air flows through narrowed breathing tubes, is a word central to asthma research and diagnosis.

Posted by

John Jones

at

9:43 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: Communication, enaction, Language, medicine

Saturday, August 26, 2006

Fists and irreducible complexity

Update: This post is a partial review of Malcolm Gladwell’s Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking. A key question in rhetoric and communication studies is how people are persuaded to act. Sometimes the act in question is overt in that it is the completion of some action; other times, the action could be implicit, in that it is the acceptance of some idea or line of reasoning as being true (or false). This latter group of actions are variously referred to as decisions or making up one’s mind. (I don’t consider these categories to be all that rigid. Consider them convenient shorthand for some temporary ideas—an argumentative place to hang your hat.) In Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking (2005), Malcolm Gladwell argues that many of our decisions are made without our conscious input, that they are the result of unconscious processes that occur independently of our considered, conscious thought.

A key question in rhetoric and communication studies is how people are persuaded to act. Sometimes the act in question is overt in that it is the completion of some action; other times, the action could be implicit, in that it is the acceptance of some idea or line of reasoning as being true (or false). This latter group of actions are variously referred to as decisions or making up one’s mind. (I don’t consider these categories to be all that rigid. Consider them convenient shorthand for some temporary ideas—an argumentative place to hang your hat.) In Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking (2005), Malcolm Gladwell argues that many of our decisions are made without our conscious input, that they are the result of unconscious processes that occur independently of our considered, conscious thought.

Many of Galdwell’s proofs for this idea come from the ideas of complexity theory and have interesting applications to rhetoric. In the first case, Gladwell references Paul Ekman and W. V. Friesen’s Facial Action Coding System (FACS) (here is a link to a brief explanation of FACS, and a FACS chart is pictured below). Ekman and Friesen documented over 10,000 configurations of the facial muscles, of which they found about 3,000 that were meaningful. This result comes from the layering of actions in the facial muscles, actions which grow exponentially as more muscles are worked together (or in sequence). The result seems very much like a strange-attractor type problem, where out of many countless meaningless results—what Gladwell calls ‘the kind of nonsense faces that children make’ (201)—a few stable meaningful results arise.

In Gladwell’s discussion of ‘thin-slicing’, his name for the ability to find emergent (my word, not his) properties of a system in very small samples of that system—say, ten seconds of a couple’s conversation is sufficient to make a highly-probably determination of that couple’s future, or a similarly small sample of Morse code is enough for a trained listener to be able to identify the operator transmitting that code. According to Galdwell, this code pattern from the second example, called a fist, ‘reveals itself in even the smallest sample of Morse code’ and ‘doesn’t change or disappear for stretches or show up only in certain words or phrases’ (29). This fact would seem to indicate that the fist is not irreducibly complex, that is, that the message is not the shortest possible way of describing the fist, for the fist shows up even in very small samples of the message.

In complexity theory, the irreducibly complex is equivalent to the random. Take the example of a random string of numbers. This string is the prototype of an irreducibly complex message because it cannot be expressed in a reduced form. The shortest method of reproducing a string of random numbers is the string itself. Language theorists like Jacques Derrida seem to argue that all symbol messages are irreducibly complex in this way, that they cannot be expressed in any shorter form than what they are, for to shorten or summarize them would be to make a different message by leaving out key information.

The fist example seems to indicate, however, that some significant portion of symbol messages, those parts that are roughly equivalent to style, are able to be reduced and maintain their identity. I’m not quite sure what the implication of this result is, but I find it interesting, especially in the context of analog and digital communication. Though Morse code is essentially a digital medium, the fist only appears as an analog aftereffect of the digital message. Similarly, Nicholson Baker’s advocation for the preservation of library card catalogs is an example of a digital message that is willing to discard analog aftereffects that are deemed unimportant.

Now, it is obvious that the digital portion of a message is also not irreducibly complex. New methods of compression might make it possible to transit the same message in a shorter form. The counterpart in communication theory, I suppose (and someone feel free to correct me if I’m getting all of these theories in a muddle), is that the iterable nature of symbol systems allows for shorthand communication of messages.

If messages are made up of both digital and analog components, neither of which are, by themselves, irreducibly complex, what then, in the Derridian sense, is the irreducible part of the message? I wonder if it is the interplay between these two elements, the connection between the analog and the digital, that is random and irreducible.

One of Gladwell’s arguments in Blink is that it is in our interest to discover where our unconscious decisions arise from as a means of determining whether or not they are to be trusted. On that note, a final thought: the analog portion of the message is much more difficult to counterfeit than the digital, though such imitation is not impossible. When all information is digitized, it is able to be copied—falsified—endlessly, much more easily than analog messages. This is because digital messages lack the global, emergent features of the reducibly complex, like the Morse code operator’s fist. As digital information is still carried via analog devices (analog telephone lines, for instance) it is possible that this portion of the signal can be analyzed for identifying features. One solution to our current concerns with digital security might be finding a way to reconnect the analog and the digital, making individual messages more difficult (perhaps impossible?) to counterfeit.

Posted by

John Jones

at

2:56 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: Communication, Complexity, Emergence, Review, Rhetoric

Thursday, July 13, 2006

Notes on chaos

This post is a pretty random group of reactions to the ideas of chaos theory presented in James Gleick’s Chaos: Making a New Science (1987).

According to previous understandings of nature, “Simple systems behave in simple ways. . . . Complex behavior implies complex causes. . . . Different systems behave differently” (303). However, chaos theory argues that “Simple systems give rise to complex behavior. Complex systems give rise to simple behavior. And most important, the laws of complexity hold universally, caring not at all for the details of a system’s constituent atoms” (304). This theory suggests that commonly held assumptions about the behavior of the world are flawed. Natural systems do not exhibit simple, linear behavior. They do, however, exhibit patterns, but these patterns are often fractal, that is, they exhibit constant change and transformation at all scales and cannot be boiled down to simple geometric shapes. An example would be the contrast between a triangle, which only gives information at one scale, and a fractal image, which exhibits more information no matter what scale you look at.

This theory suggests that commonly held assumptions about the behavior of the world are flawed. Natural systems do not exhibit simple, linear behavior. They do, however, exhibit patterns, but these patterns are often fractal, that is, they exhibit constant change and transformation at all scales and cannot be boiled down to simple geometric shapes. An example would be the contrast between a triangle, which only gives information at one scale, and a fractal image, which exhibits more information no matter what scale you look at.

“Libchaber believed that biological systems used their nonlinearity as a defense against noise. The transfer of energy by proteins, the wave motion of the heart's electricity, the nervous system—all these kept their versatility in a noisy world.” (194).

This is an interesting observation, since most communication deals at some level with the problem of overcoming noise, that is, barriers that prevent a clear understanding of the message. This phenomenon presents itself in nature as well as in language. Proposing non-linearity, the ability of seemingly chaotic systems to generate order, as a means of overcoming noise deserves more attention in studies of communication.

“the spontaneous emergence of self-organization ought to be part of physics” (252).

And everything else, I would say. The question of order pops up in a lot of scientific literature; attempting to find the answer to it is one of the things that attracts me to chaos and complexity theory. Most analytic effort is spent trying to explain the nature of order, but only recently has the origin of order taken the forefront in scientific questioning.

Posted by

John Jones

at

11:10 AM

3

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: chaos, Communication, Complexity, Emergence, information

Wednesday, July 12, 2006

Metaphor and reality

Update: This post is a partial review of Kenneth Boulding’s Ecodynamics and James Gleick’s Chaos: Making a New Science

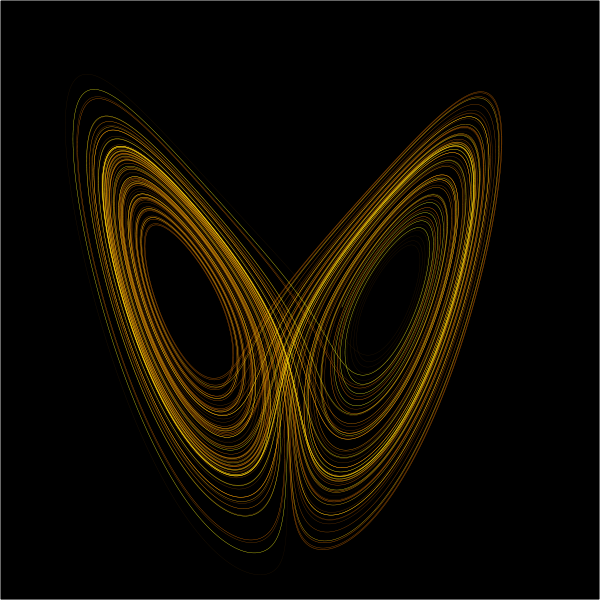

Lately I’ve been thinking a lot about the metaphors that Kenneth Boulding uses to describe the natural world in his Ecodynamics (1978). One such metaphor is evident in his statement that knowledge, or know-how, is embedded in the structure of natural objects. The way in which Boulding expresses this idea is that “in a certain sense, helium ‘knows how’ to have two electrons and hydrogen knows only how to have one” (14). This is a case where ‘structure’ has the ‘ability to “instruct”’ (13). One benefit of this particular way of looking at knowledge is that it limits what is determined about a subject to what can be known. A fact of an atom of helium is that it is an atom of helium, and that fact can be stated in terms of know-how. (Boulding uses this method to show how unhelpful the idea of the survival of the fittest is, for it really is just a statement about the survival of the survivors.) This metaphor is particularly powerful because it allows for our understanding of communication to explain natural phenomena like the replication of DNA. Know-how is communicated from the existing structure through other materials that lend themselves to communicating that structure as well. By accepting this metaphor, statements about language, the realization that “communication . . . becomes a process of complex mutuality and feedback among numbers of individuals that leads to the development of organizations, institutions, and other social structures which affect” the outside world (16). The spread of know-how through communication—the “multiplication of information structures” (101)—leads to complex behavior and organization, in persons as well as in nature. This phenomenon, communication through the propagation of order and know-how, can be seen in other natural structures. In Chaos: Making a New Science (1987), James Gleick identifies several of these phenomena like entrainment or modelocking, an example of which being when several pendulums, connected by a medium like a wooden stand that can communicate relevant information like rhythms, all swing at the same rate (293). Similarly, in the phenomena of turbulence, “each particle does not move independently”; in their interdependent interaction, the motion of each “depends very much on the motion of its neighbors” (124). I don’t think that it is much of a stretch to say that know-how is propagated through the constraints of strange attractors (the image to the left is of the Lorenz attractor) and similar phenomena. Chaotic phenomena behaves in a particular way because that is what it knows how to do.

This phenomenon, communication through the propagation of order and know-how, can be seen in other natural structures. In Chaos: Making a New Science (1987), James Gleick identifies several of these phenomena like entrainment or modelocking, an example of which being when several pendulums, connected by a medium like a wooden stand that can communicate relevant information like rhythms, all swing at the same rate (293). Similarly, in the phenomena of turbulence, “each particle does not move independently”; in their interdependent interaction, the motion of each “depends very much on the motion of its neighbors” (124). I don’t think that it is much of a stretch to say that know-how is propagated through the constraints of strange attractors (the image to the left is of the Lorenz attractor) and similar phenomena. Chaotic phenomena behaves in a particular way because that is what it knows how to do.

Supposing we can accept this metaphor for behavior in nature, that it is a kind of communication where what is being communicated is knowledge, then it seems like it would be completely reasonable to use the language of rhetoric to describe natural behavior. The sensitive interdependence of the parts of a system, recognized 1) by Boulding in animal development where “the history of a cell in an embryo depends on its position relative to others rather than its past history, because its position determines the messages”—or information—“that it gets” (107), and 2) by the physicist Doyne Farmer, who, in describing mathematical equations notes “the evolution of [a variable] must be influenced by whatever other variables it’s interacting with,” for “their values must somehow be contained in the history of that” variable (266) suggests a rhetorical way of looking at nature. As Boulding acknowledges, everything depends on everything else, a point that rhetoricians have been making about the persuasive situation since the discipline was formed. This connection opens up the exciting possibility of rhetorical analysis of natural systems, where the tools of monitoring persuasion in language could be used to track the movement of know-how through nature.

Posted by

John Jones

at

10:02 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: attractors, chaos, Communication, Complexity, information, know-how, Review, Rhetoric

Thursday, July 06, 2006

Complex Systems, hypnotism, magic

Update: This post is a review of Kenneth Boulding’s Ecodynamics: A New Theory of Societal Evolution

Bateson’s idea that communication is a replication of structure from one person to the next is also found elsewhere. In Ecodynamics (1978), Kenneth Boulding argues that the power of human communication comes from the ability of our brains—an ability for which he uses the metaphor ‘know-how’—to replicate structure across other brains (128). Boulding finds this tendency in structures like DNA, the structure of which attracts ‘a similar structure from its material environment’ and those new entities are able ‘form themselves, as it were, into a mirror image of the original molecule’ (101). Similarly, communication works by structures in one person’s ‘head’ ‘replicating’ themselves in the head of another. Or, to avoid the complications involved in going inside heads, it is the propagation of the know-how through the various structures for which it is coded.

This explanation of communication provides a partial understanding of hypnosis. In effect, hypnosis works through the physiological repression of the various means of suppressing this propagation of the code. Bateson describes this process in a circus animal, which he feels ‘abrogate[s] the use of certain higher levels’ of thinking; he argues that it is also the means of hypnotism (369). If the higher levels of intelligence are circumvented, either through the conscious will or through suggestive or physiological means, then there is no interference to prevent the code from replicating.

This realization leads to a biological explanation for effective communication. First, the code must be able to be received without interference. Second, it must have what Boulding calls the sufficient ‘material’ means to propagate (101). In the replication of DNA, this would mean the correct molecules and nutrients; In human communication, it would be effective channels by which the code could spread. Third, the code must be correctly encoded for the material in which it wishes to move. Both Bateson and Boulding suggest that magic represents an ineffective communication of this kind. If a person can be persuaded to do something by words or actions, the practitioner of magic argues, so can nature. However, nature is not designed so as to be able to receive communicative codes and is therefore not influenced by the majority of them (typically words or ritual behavior—changing the code so that it can be received by natural bodies, however, such as fertilizing a plant or seeding a cloud, does result in effect code propagation from humans to nature).

The similarities that are seen between code propagation across persons and in biological structures like DNA prompt both Bateson and Boulding to make a connection between minds and nature. Bateson points out that the basic unit of evolution—the interconnected system—is also the unit of the mind, which is not necessarily limited by the skull. Similarly, Boulding suggests that like environments, individual minds are connected through ‘writing, sculpture, painting, photography and recordings’ into a ‘single mind’ in that each individual mind ‘participates in the experience of other minds through the intermediary of communication’ (128). This fact leads to the interesting conception of the individual not as an individual, but as a part of a larger whole. Since most theories of communication are based on the first model, appropriating the second should have interesting effects on communication theory.

Posted by

John Jones

at

1:28 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: Communication, ecologies, enaction, evolution, hypnosis, know-how, materiality, Review

Monday, June 26, 2006

Communication as relationship

Update: This post is a partial review of Gregory Bateson’s Steps to an Ecology of Mind In his references to communication, Bateson provides an intriguing alternative to the prevailing model of the persuasive process. That process is largely considered to consist of an author/speaker presenting some superior content, and that content, through its effective presentation, persuading an audience of the author’s thesis. (This is certainly not the only model for communication, but I would think it is the one that most people—especially non-academics—would adhere to.) Rhetoricians would focus on the importance of the presentation, that is, all of the choices the author/speaker makes in presenting the content, but primacy would be given to the content. This formulation privileging content would not only be considered the best one, but possibly the most ethical one as well.

In his references to communication, Bateson provides an intriguing alternative to the prevailing model of the persuasive process. That process is largely considered to consist of an author/speaker presenting some superior content, and that content, through its effective presentation, persuading an audience of the author’s thesis. (This is certainly not the only model for communication, but I would think it is the one that most people—especially non-academics—would adhere to.) Rhetoricians would focus on the importance of the presentation, that is, all of the choices the author/speaker makes in presenting the content, but primacy would be given to the content. This formulation privileging content would not only be considered the best one, but possibly the most ethical one as well.

Bateson presents an alternative. Although he does not ignore the importance of content, his model of communication focuses on the presentation, what he refers to variously as “structure” or “patterns,” of that communication, rather than what is being presented, and these structures carry information about relationships. Referring to his own speech at an academic conference, Bateson remarks that his real topic “is a discussion of the patterns of [his] relationship” to the audience, even though, as he tells them, that discussion takes the form of his trying to “convince you, try to get you to see things my way, try to earn your respect, try to indicate my respect for you, challenge you” (372). In other words, the acceptance of the content is dependent upon how well he as a speaker is able to affirm that relationship. In another example, he points out that if one were to make a comment about the rain to another person, hearer would be inclined to look out the window to verify the statement. Though he notes that such behavior can seem confusing because it is redundant, this redundancy is not a question of the first speaker’s truthfulness, but rather an example of an attempt to “to test or verify the correctness of our view of our relationship to others” (132).

This patterning or structure, the need to comment on the relationship between speaker an audience by 1) conforming to arbitrary rules (another kind of structure) like those set up in an academic conference or 2) reminding ourselves that a person is a trustworthy source of information, is, to Bateson, representative of “the necessarily hierarchic structure of all communicational systems” which manifests itself in communication about communication (132). For Bateson, this realization has at least two outcomes. First, in learning it means that what is learned by the subject is often not the topic under study per se, but how “the subject is learning to orient himself to certain types of contexts, or is acquiring ‘insight’ into the contexts of problem solving,” that is, “acquir[ing] a habit of looking for contexts and sequences of one type rather than another, a habit of ‘punctuating’ the stream of events to give repetitions of a certain type a meaningful sequence” (166). Second, this means that these structures of “contexts and sequences” replicate themselves in learners, who then become audiences, and those audiences respond to recognition (perhaps the wrong word) of that structure. As Bateson says, “in all communication, there must be a relevance between the contextual structure of the message and some structuring of the recipient” for “people will respond most energetically when the context is structured to appeal to their habitual patterns of reaction” (154, 104). In these situations, what appeals to or persuades the audience is not the content, but the recognition of the familiar structure in the communication in question.

I think this focus on the structure of communication and the way in which that structure replicates itself across individuals highlights the technological dimension of speech—the way in which “meaning” is dependent upon the form of language—and has some interesting applications for the question of ethics and truthfulness in rhetoric, a topic I will comment on in my next post.

Posted by

John Jones

at

9:22 PM

3

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: Communication, Complexity, Cybernetics, Emergence, Review, Rhetoric