I first encountered The Embodied Mind

when I took Peg Syverson’s class “Minds, Texts, and Technology” during my first semester at UT in 2005. I remember being somewhat overwhelmed by it then: the authors—Francisco Varela, Evan Thompson, and Eleanor Rosch—pose a radical challenge to then-current (1991) conceptions of cognitive science. Tracing the field of cognitive science through two stages, cognitivism and emergence, the authors explain that neither of these approaches take into account the role of bodily experience in the process of perception, arguing that this experience is a necessary precondition for cognitive functions.

According to the authors, the first stage of cognitive science, cognitivism, arose in the middle of the twentieth century as an outgrowth of cybernetics. While Varela, Thompson, and Rosch felt that cybernetics was initially a rich conversation between a number of differing views of the mind and how it functions, cognitive science came to be dominated by the cognitivist paradigm. These cognitivists described cognition as merely symbol processing in the brain, processing which was enabled by the mind’s creation of representations of the outside world. However, cognitivism had a problem. According to Varela et al., researchers were unable to find biological examples of the mind’s symbol-processing, a lack which caused them to shift the location of this processing to the subconscious. In short, cognitivism required the separation of consciousness from cognition, a move which led cognitivists to posit the existence of an autonomous self—an ego or soul. However Varela, Thompson, and Rosch note that when one looks for the ego or self, the only thing that can be found is experience. They therefore claim that cognitivism failed because it tried to describe experience strictly through the means of analysis, without focusing on bodily experience.

However, cognitivism had a problem. According to Varela et al., researchers were unable to find biological examples of the mind’s symbol-processing, a lack which caused them to shift the location of this processing to the subconscious. In short, cognitivism required the separation of consciousness from cognition, a move which led cognitivists to posit the existence of an autonomous self—an ego or soul. However Varela, Thompson, and Rosch note that when one looks for the ego or self, the only thing that can be found is experience. They therefore claim that cognitivism failed because it tried to describe experience strictly through the means of analysis, without focusing on bodily experience. Emergence, or connectionism, attempted to deal with some of the problems posed by cognitivism by suggesting that the phenomena of mind emerges out of the numerous simple, biological processes that make up the brain. Because connectionism is sub-symbolic—that is, it doesn’t require symbol-processing in the mind—it was represented an advance over cognitivism because it was able to explain both symbolic behaviors and non-symbolic behaviors. Cognitive scientists found it attractive because it is close to human biology, produces workable models, and fits the dominant scientific paradigm, namely, that there is a real world out there that some subject can discover through cognition, a paradigm which emergence shares with cognitivism.

Emergence, or connectionism, attempted to deal with some of the problems posed by cognitivism by suggesting that the phenomena of mind emerges out of the numerous simple, biological processes that make up the brain. Because connectionism is sub-symbolic—that is, it doesn’t require symbol-processing in the mind—it was represented an advance over cognitivism because it was able to explain both symbolic behaviors and non-symbolic behaviors. Cognitive scientists found it attractive because it is close to human biology, produces workable models, and fits the dominant scientific paradigm, namely, that there is a real world out there that some subject can discover through cognition, a paradigm which emergence shares with cognitivism.

However, Varela, Thompson, and Rosch argue that neither cognitivism or emergence can deal with the failure of science to find the source of the self, and that both flounder when they attempt to account for the role of the outside world in cognition. According to them, western science, except for some notable attempts by Minsky, Jackendoff, and Merleau-Ponty, has chosen to completely ignore these questions.

One result of this failure to bring these two worlds together is what the authors call the Cartesian Anxiety. The Cartesian Anxiety is the separation of mind and world—subject and object—into competing subjective realties, leaving us with the feeling that there is either a stable world, or there is only representations; that is, realist and subjectivist assumptions. This is a problem for both cognitivism and connectionism because both rely on a pre-given world that is represented symbolically or sub-symbolically.

As an alternative to this approach, the authors argue that the interaction of individual perception with physical reality “brings forth a world” that is dependent on the both, rather than being independent of either. One of their primary examples of this bringing forth a world is the study of color vision. The authors demonstrate that the perception of color is dependent on the physiology of an organism (pdf) to demonstrate that the experience of the outside world is brought forth by the organism in concert with that outside world; the “world” that is experienced is dependent on both.

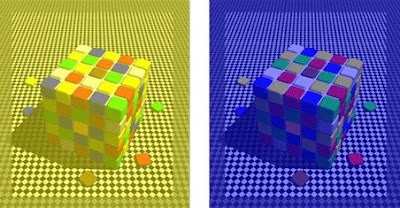

Consider, for example, these optical illusions.

The squares that appear blue in the example on the left are actually the “same” color as the squares that appear yellow in the example on the right. The reason that they appear to be separate colors in these two images is a result of the interaction of our three-dimensional color vision and the colors which surround them in the image. This particular illusion, which makes one color appear to be two, is brought forth by our physical bodies interacting with the physical world.

Results like this one prompt Varela, Thompson, and Rosch to suggest a third stage in the development of cognitive science: enaction. According to the authors, enaction posits that perception depends on bodies and that cognition is the result of recurrent patterns of perception. Only enaction is able to account for cognition without extracting the mind for actual experience. An enactionist model of cognition, then, would view the mind as existing as the result of these patterns of perception, rather than as a symbol processing machine or an emergent phenomenon that reproduces a stable outside world.

One final note. Up to this point, I haven’t really mentioned one of the authors’ major arguments in this text: that Buddhist models of conceptualizing the self and experience are superior to those of Western philosophy. It is this connection to Buddhism that suggested enaction theory to the authors. I didn’t spend much time discussing this connection here because, personally, I think enaction can stand by itself as a theory of mind. However, I’m sure that for many readers, especially in the cognitive science community, this connection could be a deal-killer that discredits the book’s entire argument (hat-tip to Jim Brown for noting this problem).

Monday, April 14, 2008

Review: Varela, Thompson, and Rosch, The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience (1991)

Posted by

John Jones

at

2:18 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: Buddhism, cognitive science, cognitivism, Emergence, enaction, Review

Monday, March 17, 2008

Review: Holland, ed. Remote Relationships in a Small World (2007)

I ran across Remote Relationships in a Small World a month or so ago in a publisher’s catalog, and I thought it looked pretty promising, seeing as my work is gravitating towards studies of social networks and mobile communication. The collection of essays are intended, according to editor Samantha Holland, to provide new research on social relationships conducted online. This, I assume, is the source of the title, which suggests that the digital age has both made the world smaller by allowing for instant communication across time and space, but at the same time that time and space is real and has a real effect on the relationships conducted online.

The three chapters that jumped out at me were Holland’s chapter (with Julie Harpin) on the use of MySpace by British teenagers, Janet Finlay and Lynette Willoughby’s study of the use of WebCT forums and blogs in online learning, and Simeon J. Yates and Eleanor Lockley’s study of male and female cell phone use. (The complete TOC can be found here.)

Holland and Harpin presented the results of a pilot study of teenage British MySpace users, following the usage habits of 12 teenagers. Their results seemed to confirm the work of boyd and Ellision (2007) in that the teenagers they studied tended to use MySpace to communicate with people they already knew socially. Additionally, the authors found that, unlike the typical stereotype of the digital loner, the social network was a “hive of sociability.”

Similarly, Finlay and Willoughby’s chatper didn’t break any new ground. They found that a minority of the (mostly male) students using their course forum and individual blogs would post offensive messages, and that this behavior tended to alienate other users. After their mostly textual case study, the authors concluded that for an online learning space to be a real community of practice there needed to be scaffolded interactions with the community so that users could become socialized to it, a feat which was not possible in their 12-week course.

Finally, Yates and Lockley examined the use of cell phones by men and women in a number of different contexts: at home, on the train, and in other public places like restaurants and coffee shops. They found that the men in their study tended to send shorter messages than the women, and that the longest messages were sent in conversations between two women. Like Holland and Harpin, the authors found that the participants in their study tended to not use their phones to contact or converse with strangers, but rather to keep in touch with people who were close to them, both physically (neighbors) and emotionally (friends and relatives).

I found this collection to be a bit of a mixed bag. While the studies I mentioned here were interesting, and had interesting conclusions, I found myself wishing they were a bit more rigorous. This was particularly the case with the Holland and Harpin and Finlay and Wiloughby chapters. While each was interesting, neither broke new ground, and both seemed to merely share the overall theme of the online texts they collected. Admittedly the Holland and Harpin study was a preliminary one, but, that being the case, I wonder why it was included in this collection.

The Yates and Lockley chapter suffered from the opposite problem. The authors used a large number of measures—surveys, observation, diary studies, focus groups—but the analysis and discussion of these measures seemed abrupt to me. I would have liked to have seen them choose some of the data to focus on with more depth and detail, rather than have them present this cornucopia of data.

That said, I found the book to be useful, not the least for the support, however tentative, that the studies included in it lend to the thesis that social communication is used more to keep in contact with people in existing social networks, rather than create new contacts. Somewhat ironically, these studies seem to suggest that our online relationships aren’t so “remote” after all.

Posted by

John Jones

at

6:49 PM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: cellphones, CMS, Communication, enaction, Mobile phone, MySpace, Online Communities, research, Review, SMS, social networking

Thursday, February 28, 2008

Wesch on collaborative research

Michael Wesch at Digital Ethnography has posted a description of a collaborative research environment developed by one of his classes.

Michael Wesch at Digital Ethnography has posted a description of a collaborative research environment developed by one of his classes.

During the first month of the semester the Digital Ethnography class of 2008 has been hard at work trying to leverage various online tools to improve our collaborative research efforts. We have managed to pull together a number of free tools into a single research platform that I think is going to work out very nicely.

Wesch then goes on to describe how he and and his students have cobbled together a shared, online environment for recording their research notes and other materials using Netvibes, Zoho, wikis, and other tools. It seems like a great setup, particularly for this application: researching digital environments.

I am curious, however, to see how similar tools will be used for other kinds of research, particularly research of non-digital subjects. Any good tool needs to be 1) suited to the task and 2) suited to the user. My suspicion is that while Wesch’s online research environment works great for digital research—for example, Wesch describes a tool for displaying online video next to a research form, the latter of which can be filled out while the video is playing—I wonder if its usefulness for other research tasks—say, traditional library research—will be somewhat limited. Some users simply don’t like to read a book in front of the computer, for instance. (Although, people’s habits are rapidly changing, so it may turn out that I’m completely wrong about this.) In short, this is a great setup for online research, but its efficacy for other kinds of research will depend on individual user’s habits and what it is they want to study.

Posted by

John Jones

at

10:03 AM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: collaboration, Digital Ethnography, enaction, Netvibes, research, Zoho

Friday, January 04, 2008

Tuesday, December 18, 2007

Writing technologies: Circumventing the keyboard

Yesterday I came across these two examples of writers working around half of the ubiquitous computer interface: the keyboard.

First, Martin A. Rice, Jr., an assistant professor at the University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown, likes to compose his emails on a typewriter:

Mr. Rice will often write a letter on his typewriter, scan it into his computer, and then send the image as an e-mail “Some people are tickled by it,” he “Some people are absolutely annoyed.”

Apparently, Rice prefers the tactile feedback of typewriter keys to the “mushy” response of a computer keyboard.

Second, novelist Richard Powers, who won the National Book Award for The Echo Maker, also dislikes typing, and in an interview on NPR’s Fresh Air explains why he likes to compose his novels using speech-recognition software instead.

The Powers interview was particularly interesting to me because I spent a summer working as an intern at Speech Technology magazine in the summer of 2000. At that time, I think it would have been extremely cumbersome to dictate a long text using speech-recognition, given the limitations of the technology back then—it demanded a lot of computing power, required users to speak using unnatural cadences so the software could distinguish between words, and users had to spend a lot of time training the software to recognize their accents and speech patterns before it was very accurate. Apparently the technology has improved quite a bit, or, at least, Powers has found a way around its limitations.

One question I had about Powers’s process that wasn’t answered in the interview was: how does he revise? Does he use the software, or does he revert to a keyboard for this part of the writing process?

Posted by

John Jones

at

2:29 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: enaction, technology, Writing, Writing process

Saturday, December 08, 2007

The Matrix Fallacy: Know-what ≠ know-how

I remember an episode of Alvin and the Chipmunks from when I was a kid, where, for some reason, the ‘munks were involved in a baseball game. At a crucial plot moment, Simon was called up to bat, and the drama of the scene came from the fact that Simon wasn’t athletic (for those of you not familiar with the characters, Simon, on the far left, was the nerdy one). However, before Simon stepped up to the plate, he took a quick moment to work out the physics of the ball’s trajectory (I can’t remember the details, but if you want to optimize the distance of a projectile, you should launch it at a 45º angle; to go a specific distance—say, over the outfield wall of a baseball field—you just need to know how much force to put behind it) and he then promptly stepped up to the plate and knocked the ball out of the park.

I remember an episode of Alvin and the Chipmunks from when I was a kid, where, for some reason, the ‘munks were involved in a baseball game. At a crucial plot moment, Simon was called up to bat, and the drama of the scene came from the fact that Simon wasn’t athletic (for those of you not familiar with the characters, Simon, on the far left, was the nerdy one). However, before Simon stepped up to the plate, he took a quick moment to work out the physics of the ball’s trajectory (I can’t remember the details, but if you want to optimize the distance of a projectile, you should launch it at a 45º angle; to go a specific distance—say, over the outfield wall of a baseball field—you just need to know how much force to put behind it) and he then promptly stepped up to the plate and knocked the ball out of the park.  Even though I couldn’t express why at the time, I knew that wasn’t right. Simon’s baseball heroics reminded me of those scenes in The Matrix where the characters have skills—karate, flying a helicopter—imported directly into their brains through the data ports in their heads, the implication being that the mere fact that they have received this information makes them able to physically perform specific tasks. However, know-what does not equal know-how.

Even though I couldn’t express why at the time, I knew that wasn’t right. Simon’s baseball heroics reminded me of those scenes in The Matrix where the characters have skills—karate, flying a helicopter—imported directly into their brains through the data ports in their heads, the implication being that the mere fact that they have received this information makes them able to physically perform specific tasks. However, know-what does not equal know-how.

I know there are examples where people have brought physical processes into coordination with abstract information; one example that comes immediately to mind is musicians with perfect pitch. With the right kind of training, a person can be taught to distinguish individual notes purely by sound or hit a ball with so many pounds of force or at a particular angle. However, the key word here is “training.” The knowledge wouldn’t be sufficient to the skill, for the skill could only be acquired through bodily training.

It seems far more likely that physical processes like hitting a baseball or kicking Agent Smith’s ass are dependent on embodiment; that is, the process is learned through the combination of the mental and physical systems of the body (see Varela, Thompson, and Rosch’s The Embodied Mind). For that reason, merely having information about something does not necessarily translate into having the skill—or know-how—to accomplish a task.

I started thinking about this recently because of Bionic Woman. On an episode from a few weeks ago, Jamie has to stop a whirling fan so Dr. Burke can practice his karate moves on terrorists. As she prepares to grab the spinning blades, we get a shot of her bionic vision, and there is a readout showing the fan’s rotation speed in m/s*s.

This struck me as another example of the Matrix Fallacy. Knowing how fast a fan is spinning doesn’t necessarily translate into knowing when to reach in and grab the blade.

I suppose you could argue that Sommers’ bionics have solved this problem for her by interfacing between her physical systems and abstract ideas like m/s*s. However, this kind of abstract processing has been the goal of AI since its inception, but has so far seemed impossible. At any rate, it would be more interesting if the show illustrated the bionic woman’s skill in ways that made more sense in light of embodiment.

Posted by

John Jones

at

12:16 PM

2

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: AI, embodiment, enaction, know-how, Matrix fallacy

Saturday, November 24, 2007

DIY ‘Minority Report’ multi-touch interface

A grad student from Carnegie Mellon named Johnny Lee has posted a video demonstrating how the Wiimote can be used to create a multi-touch, gestural interface similar to the ones seen in Minority Report.

His website has some other interesting videos showing his work with motion tracking and interfaces.

via Make blog

Posted by

John Jones

at

11:43 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: DIY, enaction, gestural interface, interface

Friday, November 23, 2007

Facebook’s Beacon ad platform: Criticism and censorship

Facebook has launched a new ad platform called “Project Beacon”:

Facebook has launched a new ad platform called “Project Beacon”:

the new program is threefold: advertisers can create branded pages, run targeted advertisements, and have access to intelligence and analytics pertaining to the site’s more than 50 million users. Partners can participate in all three components of Facebook Ads, or a combination of them. “When you put this all together, you get some pretty amazing things,” Zuckerberg said of the program, which he said took “four months or so” to develop.

Through the branded pages program, advertisers can design custom pages with information, content, and custom applications—“any application that was written for users on the Facebook Platform,” Zuckerberg explained. Facebook users can sign up as “fans” of that brand, install branded applications, and other activities that will all show up in their profiles’ “mini feeds” and on the “news feeds” that are broadcast to their friends lists.

“When people engage your page on Facebook, that’s going to spread information about your brand virally through the social graph,” Zuckerberg said. “It becomes a trusted referral.”

For MoveOn.org, this new program is going over about as well as news feeds did when they were launched. MoveOn’s Adam Green argues that the platform is “a ‘glaring violation of (Facebook’s) users’ privacy,’ and has launched a paid ad campaign on Facebook, a ‘protest group’ on the social-networking site, and an online petition to encourage the company to allow users to opt into the program at their own volition.” What bothers MoveOn is that Beacon captures online activity outside of Facebook, and then publishes that activity in the users News Feed. While it is possible to opt out of Beacon, the organization complains that the process is complicated, and has to be repeated at each Facebook partner site.

Facebook has responded to these charges, claiming that users’ privacy will not be invaded because News Feeds can only be seen by friends, and that MoveOn’s campaign has misrepresented the difficulties in opting out of the program. The sticking point here is what counts as privacy: Facebook claims that only publishing information to friends is private, while Green claims, somewhat hyperbolically, “If Facebook’s argument is that sharing private information with hundreds or thousands of someone’s closest ‘friends’ is not the same as making that information ‘public,’ that shows how weak Facebook's argument is.” On the one hand, I think Facebook is correct: it is easy to set the privacy features of the site so that the News Feed can only be seen by those you want. However, even though Green may be overstating the case with the numbers he quotes,—which seems somewhat typical of MoveOn’s emotional rhetoric, considering that their other major argument is that Facebook is ruining Christmas—I believe he is correct that users are going to be somewhat blindsided by this feature and will want to have the ability to opt out completely, at least until they get used to it.

I think this new program clearly illustrates the growing importance of Facebook as a networking tool. If people didn’t find Facebook necessary, they would abandon it, rather than try to reform it. Also, I think it suggests that Facebook needs to do some serious thinking about how it introduces new products. Between this issue and the news feed reaction, it seems obvious that the company needs to pay much more attention to how its users react to its new offerings.

Finally, there is another disturbing question related to this issue. In his post responding to MoveOn’s arguments, Josh Catone at Read/Write Web suggests that Facebook users aren’t nearly as outraged as MoveOn is making them out to be, citing as evidence the fact that he couldn’t find any Facebook groups protesting Beacon. However, Michael Arrington at Tech Crunch is suggesting that Facebook may be censoring anti-Beacon groups:

Naturally all the press on the issue led people to go to Facebook to find the group MoveOn set up to organize their opposition to Facebook’s current privacy policy on this issue.

The group, which now has over 12,000 members, could not be located via search. Yesterday a search in Facebook Groups for “Privacy” began to return an error message saying “search is currently unavailable.” But at the same time, searches for any other term yielded normal results.

If this is true, and Facebook did try to limit the spread of the group, then that should make users concerned about the role the company seems to be making for itself in the search and social networking fields.

Posted by

John Jones

at

10:21 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: advertising, Emergence, enaction, facebook, news feed, social networking, Web 2.0

Monday, November 19, 2007

Second Life not “real”; users sad, lonely deviants

Morgan Clendaniel has a new article in Good Magazine on Second Life, arguing that, as the highly-lauded next wave of the internet, the virtual world is a disappointment, going virtually (ha!) unused; except, of course, for the naughty areas. Also, Second Life aficionados are depressed (and depressing) losers.

I believe the first point is the most valid and interesting. Clendaniel points out the site’s relatively few users.

Since it launched, Second Life has been hailed as a glimpse of how we will someday interact, shop, and even live. With email and online shopping now commonplace, virtual worlds are the new cutting edge of online business and buzz. “In many ways, Second Life is the next step of the internet,” says Jeska Dzwigalski, a community manager with Linden. “[In the future], having a virtual presence will be as ubiquitous as mobile phones or email addresses or a web page is today. It’s the evolution of the internet.” Right now there are almost 9 million accounts, but at even at peak times (4 p.m. Eastern—presumably, the most avid users don’t have jobs) there are only 40,000 users logged on. That means the future of the internet is only grabbing enough people to fill a baseball stadium. While that number has been slowly growing, think about this: If just a little under 1 million users have logged in during the last 30 days, that means there are 8 million others who tried Second Life and haven’t felt any need to come back.

While Clendaniel makes some good points about the site’s usage—40,000 visitors isn’t quite up to Facebook’s or Wikipedia’s numbers—the overall tone of the article seems reactionary. For instance, consider this paragraph on the ways that Second Life inhibits social relationships:

The paradox of a virtual world is that it adds human interaction to the online experience, while at the same time making sure you never have to actually interact with anyone. Now, instead of merely buying a book on a website, you can browse a virtual bookstore along side other virtual patrons, without ever leaving your home. This logic—that you’d want to give up both the speed of online shopping and the social experience of actually shopping, that you’d want to spend time in a bookstore but not actually go to one—is depressing, to say the least. From there, it’s a small step to buying only virtual clothes for your virtual self while you sit at home in your underwear (which some people no doubt already do). The only thing you can’t get here is real-life sustenance, but with enough restaurants that deliver, you could conceivably never log out. What a future it could be.

I’m not quite sure how browsing a virtual bookstore at home in your underwear is any more depressing that browsing Amazon.com at home in your underwear. Additionally, Clendaniel doesn’t seem to understand the appeal of the site to its users. After asking one user why she doesn’t meet people in the real world, he snarks off her response (“Have you ever been to Oklahoma?”) as in-group snobbery.

The article’s biggest weakness, however, is that it is entirely based on Clendaniel’s own experience as a (new) user of Second Life. It’s hardly a scientific sample, and it makes his criticisms come off as uninformed.

Posted by

John Jones

at

11:44 AM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: Emergence, enaction, Second Life

Saturday, November 17, 2007

Teens use IM to avoid emotional communication

According to a new poll from AOL and the AP, nearly half of teenagers use instant messaging services, compared to only about 20 percent usage by adults. Interestingly, a large chunk of those teens prefer IM for communications with heavy emotional content:

An estimated 43 percent of teens who instant message use the tool for emotionally charged conversations, according to a poll from AOL and the Associated Press that was released Thursday. Those conversations might include making and breaking dates.

The poll—which questioned 410 teens and more than 800 parents—found that 22 percent of teens use IM to ask people out on a date or accept one, and 13 percent of teens use instant chat to break up. Girls are also more likely to use IM to avoid uncomfortable talks. According to the poll, about half of girls and more than a third of boys said they’ve used instant chat to say what they wouldn’t say in person.

via: CNET News Blog

Related: “Email is dead. Long live email!”

Posted by

John Jones

at

2:00 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: Communication, enaction, IM

Thursday, November 15, 2007

Email is dead. Long live email!

So, it turns out that the youth of today no longer use email, preferring the IM and chat. Oh, wait; maybe that was the youth of five years ago. At any rate:

e-mail is looking obsolete. According to a 2005 Pew study, almost half of Web-using teenagers prefer to chat with friends via instant messaging rather than e-mail. Last year, comScore reported that teen e-mail use was down 8 percent, compared with a 6 percent increase in e-mailing for users of all ages. As mobile phones and sites like Twitter and Facebook have become more popular, those old Yahoo! and Hotmail accounts increasingly lie dormant.

However, there is some hope for email yet. Apparently Yahoo and Google are attempting to reanimate email’s rotting corpse as the backbone of their respective social networking strategies. Clearly, people still get worked up about email, but it is possible that, over time, email will morph into a primarily business communication tool, as the most formal—or, perhaps, the oldest and therefore least scary—of online communication methods.

Posted by

John Jones

at

11:40 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: Communication, email, Emergence, enaction, facebook, Google, IM, social networking, Twitter, Yahoo

Tuesday, October 23, 2007

The New York Times on microblogging, GPS, and privacy

Two new pieces in The New York Times by Ivar Ekman and Laura M. Holson discuss the looming possibility of our cellphones being used to track our every move. In the first, Ekman reports how Google’s recent purchase of Jaiku could set up the search giant to acquire vast amounts of information about users. Here’s a quote from the article describing what Jaiku does:

Two new pieces in The New York Times by Ivar Ekman and Laura M. Holson discuss the looming possibility of our cellphones being used to track our every move. In the first, Ekman reports how Google’s recent purchase of Jaiku could set up the search giant to acquire vast amounts of information about users. Here’s a quote from the article describing what Jaiku does:

Petteri Koponen, one of the two founders of Jaiku, described the service as a “holistic view of a person’s life,” rather than just short posts. “We extract a lot of information automatically, especially from mobile phones,” Mr. Koponen said from Mountain View, Calif., where the company is being integrated into Google. “This kind of information paints a picture of what a person is thinking or doing.”

Ekman points out that it is this automation—and its connection to “what a person is thinking or doing”—in the hands of Google that worries some people.![]() In the second article, Holson describes one instantiation of this mobile data-collection: GPS tracking with cellphones. A number of cellphone carriers now offer a service where their subscribers can show their location to other users and see those users’ locations as well. Typically, the services allow users to add and block other individuals from seeing their location on a person-by-person basis. Holson points out that the ethics of this practice are only emerging slowly—there are some people who users wouldn’t want to know their location, like bosses or spouses, but others, like close friends, who users would never think of blocking from the service.

In the second article, Holson describes one instantiation of this mobile data-collection: GPS tracking with cellphones. A number of cellphone carriers now offer a service where their subscribers can show their location to other users and see those users’ locations as well. Typically, the services allow users to add and block other individuals from seeing their location on a person-by-person basis. Holson points out that the ethics of this practice are only emerging slowly—there are some people who users wouldn’t want to know their location, like bosses or spouses, but others, like close friends, who users would never think of blocking from the service.

Posted by

John Jones

at

9:42 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: cellphones, Emergence, enaction, everyware, Google, GPS, microblogging, privacy, Surveillance, ubicomp

Saturday, October 20, 2007

How to geotag photos in Flickr

Gordon Haff at the CNET News blog has posted a description of how GPS data can be synced up with Flickr photos. It involves using a couple of free utilities to merge the GPS data with your photos, but it looks relatively painless. Of course, it won’t be necessary once cameras with built-in GPS are the norm.

Gordon Haff at the CNET News blog has posted a description of how GPS data can be synced up with Flickr photos. It involves using a couple of free utilities to merge the GPS data with your photos, but it looks relatively painless. Of course, it won’t be necessary once cameras with built-in GPS are the norm.

Posted by

John Jones

at

12:57 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: embodiment, enaction, everyware, Flickr, geotagging, ubicomp

Thursday, October 18, 2007

Chronicle.com: Second Life rules!

The folks at the The Chronicle’s Wired Campus Blog has sure been interested in Second Life lately. Well, me too.

The first post describes a new “orientation island” where new visitors to the virtual world learn what it is about. The New Media Consortium has built their own orientation island, apparently because Linden Labs’ version doesn’t do that great a job in explaining some of the features of Second Life.

The second post summarizes Peter Ludlow’s interview with MIT Press. In the interview, Ludlow claims that Second Life is run by the “Greek God method.”

There’s no really set established policy, but they refuse to be completely hands off, too. So they reach in like Greek gods reaching down from Mount Olympus, and they dabble in stuff and screw around and get involved to bail out their friends. . . . It would be much better if they just stayed out completely because then there would be an opportunity for users to create their own governance structures.

This kind of outspoken political critique is par for the course for Ludlow. The Wired Campus Blog reports that he was kicked out of the Sims Online for criticizing the governance structure there.

I’m sympathetic with Ludlow’s desire to see what would happen if Second Lifers could rule themselves, but right now I wonder if the connections between virtual worlds and the real world are too close for Linden to allow something like that. They have an interest in keeping the site somewhat similar to the real world.

Posted by

John Jones

at

7:40 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: enaction, HCI, interface, posthuman, Second Life

Wednesday, October 17, 2007

Michael Wesch’s “Information R/evolution”

Michael Wesch of “The Machine is Us/ing Us” has posted a new video “Information R/evolution.”

I think the thing to take away from the video is that information is now free of the desktop metaphor. Early in the video, he slams Yahoo for making a “shelf” online, and he celebrates that now information can be in multiple “places.” This is hardly a new thought, but the presentation is accessible and a good conversation starter.

However, like with “The Machine is Us,” I have to take issue with the assumptions of Wesch’s new work. He asserts that the web makes it possible to have information without materiality, going so far as to claim that “we organize information without material constraints.” I get his point—the next bit of text points out that he has put the same bit of “information” in “three ‘places’ at once”—but that doesn’t make the data immaterial. As Katherine Hayles points out, no information is immaterial; it exists as magnetic states on hard drives and has to be accessed with computers via cables.

Anyway, Wesch does interesting stuff. And the soundtrack is awesome.

via Searchblog

Posted by

John Jones

at

8:21 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: enaction, information, materiality, posthuman, technology, Web 2.0

Monday, October 08, 2007

Ass-mar

Apparently, doctors have a hard time treating Spanish-speaking patients with asthma because there is no word for “wheeze” in Spanish.

From The New York Times:

According to a survey conducted by asthma specialists at Columbia University Medical Center, which is situated in the heavily Dominican neighborhood of Washington Heights, there is no precise translation for the word “wheeze.”

In interviews with 39 Spanish speakers, “wheeze” was translated into 12 different Spanish expressions, including “tight chest,” “suffocation,” “asphyxiation,” “snoring” and “congested breathing.” (Nine of the respondents could not come up with any translation at all). While accredited translators came up with the term “ronquido” or “sibilancia,” only 6 of the 39 agreed with that “ronquido” and none agreed with “sibilancia” (even though that seems to be the choice of many readers here; see the comments below).

Wheezing, which according to the National Institutes of Health is a high-pitched whistling sound during breathing that often occurs when air flows through narrowed breathing tubes, is a word central to asthma research and diagnosis.

Posted by

John Jones

at

9:43 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: Communication, enaction, Language, medicine

Thursday, October 04, 2007

Evolution of Wikipedia

Brock Read at The Wired Campus has made the argument that now that Wikipedia has grown to 2,000,000 articles, the site has switched from primarily adding content to policing and editing content. According to K. G. Schneider, Wikipedia has entered its “awkward adolescence” where, Read notes, “‘inclusionists’ (who argue that the site should continue to encourage new entries) and its ‘deletionists’ (who advocate cutting articles deemed fatuous or picayune) are now engaged in a pitched battle” over what kind of content should be in the encyclopedia. Read notes an interesting example where founder Jimmy Wales’s article on Mzoli’s, a butcher shop, was deleted and then reinstated in a flurry of debate.

Inclusionists may take the evolution of the article as evidence that some quality-obsessed administrators are overstepping their bounds. But deletionists could argue just as easily that the site’s rough-and-tumble editing worked: Wikipedians decided that Mzoli’s is noteworthy, so the article lived to see another day. Are Wikipedia’s editing wars signs of a looming crisis, as Ms. Schneider seems to suggest? Or are they just examples of healthy debate?

I would argue that the debate is one over what Wikipedia is, where deletionists are fighting to keep the site in the mold of the traditional encyclopedia, while inclusionists are open to seeing the site evolve into a new kind of information depository. I have a hard time believing that the deletionists are going to win this one, or that the growth of Wikipedia is going to stall for long. When the inclusionists win—as I think they will—the site will continue to add topics covering more informational ground—local information, cultural fads, obscure knowledge—perhaps changing what we think is “ fatuous or picayune.”

Posted by

John Jones

at

11:28 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: distribution, Emergence, enaction, Wikipedia

Brain-to-machine algorithm

Researchers at MIT have developed an algorithm whereby paralyzed individuals can control prosthetic devices with their brains.

Researchers at MIT have developed an algorithm whereby paralyzed individuals can control prosthetic devices with their brains.

Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology said Wednesday that they've developed an algorithm for a neural prosthetic aid that can link an individual's brain activity to the person's intentions; and then translate that intention into movement.

Of course, other scientists have already done that, and built prototypes for neural brain-to-machine devices that can work for animals or humans. But each team has taken a different approach to the problem, such as developing algorithms for measuring activity in a specific brain region, or measuring them through EEGs vs. optical imaging.

MIT said that it has developed a unified algorithm that can work within the parameters of these different approaches. Lakshminarayan "Ram" Srinivasan, lead author of a paper on the subject, said MIT's new graphical models are applicable no matter what measurement technique is used.

via CNET News Blog

Posted by

John Jones

at

11:05 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Thursday, September 27, 2007

Web 2.0 v. laziness

Seth Porges at CrunchGear is arguing that the Web 2.0 “bubble” is going to burst when people get too lazy to continue to supply the sweet, sweet collective intelligence it needs to survive. As Porges points out, “without your neighbor/classmate/sister/girlfriend’s tireless devotion to keeping her profile up-to-date, MySpace would merely be a place for FOX to promote its properties.”

This is an interesting argument, but I’m not sure the examples Porges gives are all that convincing. The test case is Porges’s own migration through the social networking sites: Friendster used to be cool, but soon after joining up, Porges ignored his account there and moved over to MySpace. Then, when he grew too old for the highschool-yearbook vibe at MySpace, he moved over to Facebook, the country club of social networking. According to him, this same wanderlust and ennui is going to hit Digg and Wikipedia soon, causing them to fold.

This may be all well and good for Porges, but it doesn’t seem to fit the facts. As of this post, MySpace is ranked 6th in internet traffic. Additionally, Wikipeida just added its 2,000,000th English article. While I think the argument might apply to social networking sites—they depend on a critical mass of users, and if that mass moves somewhere else, they fold—it doesn’t appear to be affecting MySpace; both it and Facebook are continuing to grow. Further, and more importantly, what people do on Wikipedia and Digg is extremely different from what they do on MySpace and Facebook. I’m not sure that even a competing internet encyclopedia would cause users to leave Wikipedia. Porges himself points out that social networking sites appeal to different crowds—even Friendster is seeing a resurgance in Asia. If a competing encyclopeida emerged, it would likely have a completely different user base and produce a different kind of product. In short, I don’t buy Porges’s argument. Laziness isn’t going to bring down Web 2.0.

Posted by

John Jones

at

8:25 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: distribution, Emergence, enaction, social networking, Web 2.0

Saturday, July 29, 2006

Top-Down

Update: This post is a partial review of Stuart Kauffman’s At Home in the Universe: The Search for Laws of Self-Organization and Complexity In At Home in the Universe Kauffman cites the Cambrian explosion—the appearance of an abundance of new life forms during the Cambrian period—as an example of a phenomenon that is difficult to explain using only the theory of natural selection. Natural selection suggests that gradual changes over time slowly accrue, allowing for the development of fitter organisms. This idea, however, is difficult to map onto the relatively rapid appearance of many different body plans during that period. A more selection-friendly period, Kauffman notes, is the rebound from the Permian extinction, when “96 percent of all species disappeared” (13). After the Permian the divergence in body plans, or phyla, basically ended. While there were “many new families, a few new orders, [and] one new class” that appeared at that time, there were no new phyla.

In At Home in the Universe Kauffman cites the Cambrian explosion—the appearance of an abundance of new life forms during the Cambrian period—as an example of a phenomenon that is difficult to explain using only the theory of natural selection. Natural selection suggests that gradual changes over time slowly accrue, allowing for the development of fitter organisms. This idea, however, is difficult to map onto the relatively rapid appearance of many different body plans during that period. A more selection-friendly period, Kauffman notes, is the rebound from the Permian extinction, when “96 percent of all species disappeared” (13). After the Permian the divergence in body plans, or phyla, basically ended. While there were “many new families, a few new orders, [and] one new class” that appeared at that time, there were no new phyla.

Kauffman refers to the Cambrian explosion as a top-down event—the rapid appearance of many wildly divergent kinds of organisms—while he calls the rebound from the Permian extinction—where there were many changes in the makeup of different organisms, but no new body plans—a bottom-up event (13). This movement from top-down to bottom-up events is typical, according to Kauffman, and is also seen in technological innovations, where an initial period of discovery is followed by an explosion of variations that later settle down into a few distinct, usually optimum, plans. The “branchings of life” that this particular view exhibits follows what Kauffman feels to be a lawful pattern—”dramatic at first, then dwindling to twiddling with details later”, what he calls a “complexity catastrophe” (14, 194). This catastrophe explains how “the more complex an organism, the more difficult it is to make and accumulate useful drastic changes through natural selection”, for “As the number of genes increases, long-jump adaptations becomes less and less fruitful” (194-95).

This process of organization comes from the tendency of “complex chemical systems” to become autocatalytic, that is exhibit a “self-maintaining and self-reproducing metabolism”, and it allows the process of ontogeny, where at division cells differentiate for different purposes (47, 50). In the first case, Kauffman demonstrates with Boolean networks how autocatalysis occurs naturally in chemical systems. The image on the right shows “a Boolean network with two inputs per node” where “colors represent the state of a node” as being on or off. Using a sparsely-connected network like this to model simple chemical reactions, Kauffman shows that “when the number of different kinds of molecules in a chemical soup passes a certain threshold, a self-sustaining network of reactions”, or autocatalysis, “will suddenly appear” (47). Kauffman argues that his behavior on the part of these chemical systems is completely expected, and therefore not mysterious, as many attempts to explain it imply. Kauffman’s Boolean networks show that “when a large enough number of reactions are catalyzed in a chemical reaction of system, a vast web of catalyzed reactions will suddenly crystallize”, a property that is completely expected (50).

In the first case, Kauffman demonstrates with Boolean networks how autocatalysis occurs naturally in chemical systems. The image on the right shows “a Boolean network with two inputs per node” where “colors represent the state of a node” as being on or off. Using a sparsely-connected network like this to model simple chemical reactions, Kauffman shows that “when the number of different kinds of molecules in a chemical soup passes a certain threshold, a self-sustaining network of reactions”, or autocatalysis, “will suddenly appear” (47). Kauffman argues that his behavior on the part of these chemical systems is completely expected, and therefore not mysterious, as many attempts to explain it imply. Kauffman’s Boolean networks show that “when a large enough number of reactions are catalyzed in a chemical reaction of system, a vast web of catalyzed reactions will suddenly crystallize”, a property that is completely expected (50).

These complex behaviors also explain ontogeny. The tendency of complex chemical systems to organize themselves into auto-catalytic systems leads to those systems settling into a few attractors (see Order for Free for a discussion of attractors in biological systems), a result that allows the cells to differentiate but only in limited ways. As cells branch out to become particular kinds of cells in the organism, their tendency to stay in the basin of the attractor keeps them from becoming disordered, yet allows them to continue to propagate themselves. Order, then, from both the top-down and the bottom-up, is “vast and generative” and “arises naturally” out of common chemical interactions (25).

Posted by

John Jones

at

4:22 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: Complexity, Emergence, enaction, Review

![Wikipedia [citation needed] sticker in a bathroom](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhHZ62oj8RxE8sr-COe4DBM5N6m8mjot3MTDthCK7NWKZuWZlERpor_KNeib8cbFJDnI_8Qh_Ip4o8hIUkAiq5aE4eud0S6ZPdhsRETvFcSQrDh2eBKwFlLeI_bbi4xODUtM_Lx/s1600/200801021113.jpg)