I first encountered The Embodied Mind

when I took Peg Syverson’s class “Minds, Texts, and Technology” during my first semester at UT in 2005. I remember being somewhat overwhelmed by it then: the authors—Francisco Varela, Evan Thompson, and Eleanor Rosch—pose a radical challenge to then-current (1991) conceptions of cognitive science. Tracing the field of cognitive science through two stages, cognitivism and emergence, the authors explain that neither of these approaches take into account the role of bodily experience in the process of perception, arguing that this experience is a necessary precondition for cognitive functions.

According to the authors, the first stage of cognitive science, cognitivism, arose in the middle of the twentieth century as an outgrowth of cybernetics. While Varela, Thompson, and Rosch felt that cybernetics was initially a rich conversation between a number of differing views of the mind and how it functions, cognitive science came to be dominated by the cognitivist paradigm. These cognitivists described cognition as merely symbol processing in the brain, processing which was enabled by the mind’s creation of representations of the outside world. However, cognitivism had a problem. According to Varela et al., researchers were unable to find biological examples of the mind’s symbol-processing, a lack which caused them to shift the location of this processing to the subconscious. In short, cognitivism required the separation of consciousness from cognition, a move which led cognitivists to posit the existence of an autonomous self—an ego or soul. However Varela, Thompson, and Rosch note that when one looks for the ego or self, the only thing that can be found is experience. They therefore claim that cognitivism failed because it tried to describe experience strictly through the means of analysis, without focusing on bodily experience.

However, cognitivism had a problem. According to Varela et al., researchers were unable to find biological examples of the mind’s symbol-processing, a lack which caused them to shift the location of this processing to the subconscious. In short, cognitivism required the separation of consciousness from cognition, a move which led cognitivists to posit the existence of an autonomous self—an ego or soul. However Varela, Thompson, and Rosch note that when one looks for the ego or self, the only thing that can be found is experience. They therefore claim that cognitivism failed because it tried to describe experience strictly through the means of analysis, without focusing on bodily experience. Emergence, or connectionism, attempted to deal with some of the problems posed by cognitivism by suggesting that the phenomena of mind emerges out of the numerous simple, biological processes that make up the brain. Because connectionism is sub-symbolic—that is, it doesn’t require symbol-processing in the mind—it was represented an advance over cognitivism because it was able to explain both symbolic behaviors and non-symbolic behaviors. Cognitive scientists found it attractive because it is close to human biology, produces workable models, and fits the dominant scientific paradigm, namely, that there is a real world out there that some subject can discover through cognition, a paradigm which emergence shares with cognitivism.

Emergence, or connectionism, attempted to deal with some of the problems posed by cognitivism by suggesting that the phenomena of mind emerges out of the numerous simple, biological processes that make up the brain. Because connectionism is sub-symbolic—that is, it doesn’t require symbol-processing in the mind—it was represented an advance over cognitivism because it was able to explain both symbolic behaviors and non-symbolic behaviors. Cognitive scientists found it attractive because it is close to human biology, produces workable models, and fits the dominant scientific paradigm, namely, that there is a real world out there that some subject can discover through cognition, a paradigm which emergence shares with cognitivism.

However, Varela, Thompson, and Rosch argue that neither cognitivism or emergence can deal with the failure of science to find the source of the self, and that both flounder when they attempt to account for the role of the outside world in cognition. According to them, western science, except for some notable attempts by Minsky, Jackendoff, and Merleau-Ponty, has chosen to completely ignore these questions.

One result of this failure to bring these two worlds together is what the authors call the Cartesian Anxiety. The Cartesian Anxiety is the separation of mind and world—subject and object—into competing subjective realties, leaving us with the feeling that there is either a stable world, or there is only representations; that is, realist and subjectivist assumptions. This is a problem for both cognitivism and connectionism because both rely on a pre-given world that is represented symbolically or sub-symbolically.

As an alternative to this approach, the authors argue that the interaction of individual perception with physical reality “brings forth a world” that is dependent on the both, rather than being independent of either. One of their primary examples of this bringing forth a world is the study of color vision. The authors demonstrate that the perception of color is dependent on the physiology of an organism (pdf) to demonstrate that the experience of the outside world is brought forth by the organism in concert with that outside world; the “world” that is experienced is dependent on both.

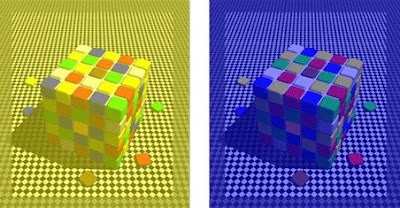

Consider, for example, these optical illusions.

The squares that appear blue in the example on the left are actually the “same” color as the squares that appear yellow in the example on the right. The reason that they appear to be separate colors in these two images is a result of the interaction of our three-dimensional color vision and the colors which surround them in the image. This particular illusion, which makes one color appear to be two, is brought forth by our physical bodies interacting with the physical world.

Results like this one prompt Varela, Thompson, and Rosch to suggest a third stage in the development of cognitive science: enaction. According to the authors, enaction posits that perception depends on bodies and that cognition is the result of recurrent patterns of perception. Only enaction is able to account for cognition without extracting the mind for actual experience. An enactionist model of cognition, then, would view the mind as existing as the result of these patterns of perception, rather than as a symbol processing machine or an emergent phenomenon that reproduces a stable outside world.

One final note. Up to this point, I haven’t really mentioned one of the authors’ major arguments in this text: that Buddhist models of conceptualizing the self and experience are superior to those of Western philosophy. It is this connection to Buddhism that suggested enaction theory to the authors. I didn’t spend much time discussing this connection here because, personally, I think enaction can stand by itself as a theory of mind. However, I’m sure that for many readers, especially in the cognitive science community, this connection could be a deal-killer that discredits the book’s entire argument (hat-tip to Jim Brown for noting this problem).

Monday, April 14, 2008

Review: Varela, Thompson, and Rosch, The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience (1991)

Posted by

John Jones

at

2:18 PM

![]()

![]()

Tags: Buddhism, cognitive science, cognitivism, Emergence, enaction, Review

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment