I’m starting to review texts for the computers and writing course I hope to teach in the fall (RHE 312), and I recently reread Adam Greenfield’s Everyware: The Dawning Age of Ubiquitous Computing (2006). The primary innovation of Greenfield’s book is, rather than there being just one model of ubiquitous or pervasive computing (ubicomp) there are in fact many “ubiquitous computings,” and that these ubicomps will combine to form an all-encompassing paradigm of distributed computing, communication, networking, and information gathering/retrieval which he calls “everyware.”

One unique feature of this book is Greenfield’s reaction to ubiquitous technology. It seems like the typical reaction to new technology (see genetic modification and nanotechnology) is to question the ethics of using/adopting it and to call for a halt to this use/adoption so its long-term effects can be contemplated. Greenfield, however, simply declares that everyware is inevitable, and that our best efforts will be spent in working toward altering its eventual appearance, rather than trying to prevent it.

In Section 3, “What’s driving the emergence of everyware?”, Greenfield examines the reasons for this inevitability. His argument is essentially twofold: first, he claism that at the moment our technology became digital, and devices were able to communicate with each other in a common language of ones and zeros, that the communication and interoperability on which everyware depends was a foregone conclusion. Further, Greenfield argues that the architecture and capabilities of many current technologies—RFID tags, the continuing development of computer chips, wireless computing—all contain the latent possibility of everyware. As he puts it, a technology like RFID “wants” to be connected to everything so as to provide a bridge between atoms and bits. Second, he argues that everyware is inevitable because it is both embedded in our collective imaginations in the form of science fiction and a workable solution to many of our looming problems, such as dealing with the move of the baby-boom generation into old age and the need of corporations for ever-increasing economic expansion.

Another thing I liked about the book is that Greenfield captures the complexity and contradictions inherent in ubiquitous systems. Everyware is divided into seven sections, and each section is made up of “theses” introduced by short, declarative statements (“Thesis 05: At its most refined, everyware can be understood as information processing dissolving into behavior.”), which are then explained, expanded on, or defended over the course of a few pages. While the sections gather the theses into larger arguments, I think they allow Greenfield to not force an extreme level of coherence on a topic whose edges are still coming into view.

To me, the two most interesting sections of the book are the first two (Google Books has the complete TOC). In these sections, Greenfield defines everyware and explains how it is unique from other instantiations of computing. As I noted above, he argues that everyware is not the same as ubicomp, but is rather a paradigm which contains many ubicomps. According to Greenfield, the everyware paradigm is the interconnection of various technologies and processes so that the computing experience will no longer be centered on a desktop or laptop machine, but will be a continuous experience of information retrieval (and encoding) via technology embedded in our surroundings. As part of this process, the bridging of the divide between data and the lived world will be key to the development of everyware.

One of his most striking pronouncements is that everyware will transform behavior into information, or, as he puts it, everyware represents the “colonization of everyday life by information technology.” Greenfield recognizes the emergent qualities of the combination of ubiquitous computing and society. Everyware is different from regular computing in that it is centered on the user and the environment. It is contextual and experiential, rather than a group of tasks like information retrieval. It does not have users—although it might have subjects. It is relational, and, as such, it has the possibility of yoking together a number of technologies and systems that we are already familiar with so that they become greater than the sum of their parts. Further, these connections will result in outcomes and effects that will be completely unforeseen.

In the book’s second section, Greenfield describes how everyware is unique. According to Greenfield, the combination of ubiquitous technologies on which everyware is based, fostered by digital connections and their inherent relational structures, will lead to emergent outcomes. That is, it will not be possible to completely foresee the results of this technology interacting together, and this fact virtually guarantees that the result will be unique. (Which would make pausing the development of the technologies everyware depends on so we can contemplate their use virtually pointless.)

Conclusion: Everyware is a good, non-technical introduction to the issues affecting the development of ubiquitous computing. I think it would be a good text for introducing undergrads to the opportunities and problems associated with new, distributed computing models.

Wednesday, January 16, 2008

Review: Adam Greenfield, Everyware: The Dawning Age of Ubiquitous Computing (2006)

Wednesday, November 14, 2007

Finally: Targeted ads for your alarm clock

This is just what I’ve always wanted:

The simplest way to describe the Chumby is as an Internet-enabled alarm clock. It actually is a Linux-powered, WiFi-connected computer with a touchscreen in a palm-sized bean bag that is intended to replace your alarm clock.

You connect the Chumby to your home’s wireless network and then configure it from the company’s website by selecting various software widgets and organizing them into channels which then cycle endlessly on your Chumby’s 3.5-inch color LCD display.

...

the terms-of-use on the Chumby Website reserves the right for the company to insert its own widgets (a.k.a. advertisements) into my widget stream. Like everybody else in the Web 2.0 era, Chumby is hoping to subsidize its business and the Chumby network by selling ads.

Posted by

John Jones

at

10:29 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: advertising, everyware, ubicomp

Sunday, November 11, 2007

Doonesbury on classroom communication

I found today’s Doonesbury to be particularly funny.

For me, the strip works on two levels. First, I think Doonesbury is poking fun at the way young people interact with technology, rather than suggesting that technology in the classroom is a wonderful thing. As evidence for this perspective I would suggest the joke in the throwaway panels—Zipper appears to be busily engaged in some sort of heavy thinking which overwhelms him, but this activity is revealed in the last panel to be checking his email—and the fact that Zipper is not the brightest character in the strip. I found the comic funny at this intended level: Zipper is clearly not participating in the class, and his scheme for avoiding being called out on this point makes for an ironically-exciting narrative.

(Personal note: this situation reminded me of my own college experience. When I was a freshman, I would regularly sit in the back of a large, required survey course and read the newspaper. On one occasion, I didn’t hear the professor when he called on me to recite something or other. When a friend a few rows over got my attention and let me know what had happened, I jump up to do the reading, but the professor had moved on to something else, so I stood sheepishly for five minutes until he finally acknowledged me.)

The comic also works for me at another level, one where Zip is able to use his considerable techno-savvy to deal with the age-old problem of being called on to answer a question about material you haven’t studied. Zipper is merely using his laptop—IM and Google—to provide a novel means for achieving an old solution: getting the answer from someone else. And, in this case, because he found the answer himself, it is more likely that he will remember it.

I’m generally amused by professors who don’t allow laptops in their classes because they “distract” the students too much. Do professors think that all the students without laptops are paying attention? Did they never pass notes, or sleep, or read newspapers in class? At least in Zipper’s case, he is able to use his distraction as part of the classroom environment, even though he isn’t completely engaged with that environment.

Tuesday, October 23, 2007

The New York Times on microblogging, GPS, and privacy

Two new pieces in The New York Times by Ivar Ekman and Laura M. Holson discuss the looming possibility of our cellphones being used to track our every move. In the first, Ekman reports how Google’s recent purchase of Jaiku could set up the search giant to acquire vast amounts of information about users. Here’s a quote from the article describing what Jaiku does:

Two new pieces in The New York Times by Ivar Ekman and Laura M. Holson discuss the looming possibility of our cellphones being used to track our every move. In the first, Ekman reports how Google’s recent purchase of Jaiku could set up the search giant to acquire vast amounts of information about users. Here’s a quote from the article describing what Jaiku does:

Petteri Koponen, one of the two founders of Jaiku, described the service as a “holistic view of a person’s life,” rather than just short posts. “We extract a lot of information automatically, especially from mobile phones,” Mr. Koponen said from Mountain View, Calif., where the company is being integrated into Google. “This kind of information paints a picture of what a person is thinking or doing.”

Ekman points out that it is this automation—and its connection to “what a person is thinking or doing”—in the hands of Google that worries some people.![]() In the second article, Holson describes one instantiation of this mobile data-collection: GPS tracking with cellphones. A number of cellphone carriers now offer a service where their subscribers can show their location to other users and see those users’ locations as well. Typically, the services allow users to add and block other individuals from seeing their location on a person-by-person basis. Holson points out that the ethics of this practice are only emerging slowly—there are some people who users wouldn’t want to know their location, like bosses or spouses, but others, like close friends, who users would never think of blocking from the service.

In the second article, Holson describes one instantiation of this mobile data-collection: GPS tracking with cellphones. A number of cellphone carriers now offer a service where their subscribers can show their location to other users and see those users’ locations as well. Typically, the services allow users to add and block other individuals from seeing their location on a person-by-person basis. Holson points out that the ethics of this practice are only emerging slowly—there are some people who users wouldn’t want to know their location, like bosses or spouses, but others, like close friends, who users would never think of blocking from the service.

Posted by

John Jones

at

9:42 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: cellphones, Emergence, enaction, everyware, Google, GPS, microblogging, privacy, Surveillance, ubicomp

Saturday, October 20, 2007

How to geotag photos in Flickr

Gordon Haff at the CNET News blog has posted a description of how GPS data can be synced up with Flickr photos. It involves using a couple of free utilities to merge the GPS data with your photos, but it looks relatively painless. Of course, it won’t be necessary once cameras with built-in GPS are the norm.

Gordon Haff at the CNET News blog has posted a description of how GPS data can be synced up with Flickr photos. It involves using a couple of free utilities to merge the GPS data with your photos, but it looks relatively painless. Of course, it won’t be necessary once cameras with built-in GPS are the norm.

Posted by

John Jones

at

12:57 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: embodiment, enaction, everyware, Flickr, geotagging, ubicomp

Monday, October 15, 2007

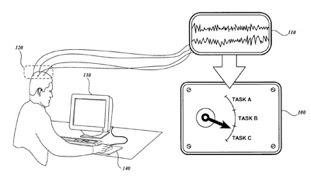

Computer-brain interaction

Today I saw two interesting stories dealing with computers and the brain. The first described a patent that Microsoft had applied for outlining a device that would measure brain waves while a subject tried out the company’s interfaces. The second story described a device for controlling a Second Life avatar using brainwaves. See a video of it in action below:

I think both are examples of rudimentary methods for bridging the gap between the physical world of atoms and the digital world of data. While there may be great uses for this kind of technology—who doesn’t want Microsoft to make better interfaces? who wants to use their hands to move a Second Life avatar?—both also suggest the ways that this kind of data can be mined for ends that nobody—particularly the user—can foresee. It will be fascinating to see how the public reacts to this technology.

via Boing Boing and Boing Boing

Related: Brain-to-machine algorithm

Posted by

John Jones

at

11:15 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: data-mining, everyware, HCI, Microsoft, Mind, neuroscience, Second Life, Surveillance, ubicomp

Thursday, October 04, 2007

Brain-to-machine algorithm

Researchers at MIT have developed an algorithm whereby paralyzed individuals can control prosthetic devices with their brains.

Researchers at MIT have developed an algorithm whereby paralyzed individuals can control prosthetic devices with their brains.

Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology said Wednesday that they've developed an algorithm for a neural prosthetic aid that can link an individual's brain activity to the person's intentions; and then translate that intention into movement.

Of course, other scientists have already done that, and built prototypes for neural brain-to-machine devices that can work for animals or humans. But each team has taken a different approach to the problem, such as developing algorithms for measuring activity in a specific brain region, or measuring them through EEGs vs. optical imaging.

MIT said that it has developed a unified algorithm that can work within the parameters of these different approaches. Lakshminarayan "Ram" Srinivasan, lead author of a paper on the subject, said MIT's new graphical models are applicable no matter what measurement technique is used.

via CNET News Blog

Posted by

John Jones

at

11:05 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Wednesday, September 26, 2007

Predicting the future

A few weeks ago, Richard MacManus at Read/Write Web posted a list of ten future web trends. At the time, I didn’t take much notice because the list was pretty standard and not very interesting to me. However, yesterday MacManus posted a follow-up article where he listed trends that users had mentioned in the comments to his previous post. It’s interesting to compare the two lists; for instance, MacManus lists boring web trends that will never happen (the semantic web), while his readers list pretty interesting web trends that will never happen (intelligent agents).

All jokes aside, both lists are also intriguing for their attempts at prognosticating the development of future technologies. I’m always fascinated by this behavior: on the one hand, the prognostications are always somewhat off, but, on the other, futurism has an effect on what kinds of technologies are developed. MacManus mentions the history of AI in his first post, noting that it has been a goal of computing since the 1950s. However, there is been practically no progress in the field. Most of the examples MacManus lists are actually human intelligence being connected through computers, as with Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. The only true attempt at AI that is mentioned is Numenta, which is attempting to build computers based on (what sounds like) a connectionist, neural network model. I don’t think that this model is much of an improvement (at least as far as AI is concerned) on the cognitivism model which computers are based on now, so I would be surprised if it led to true AI, but it is an attempt at something new. The point is, the holy grail of AI has been desired for years, even though it hasn’t been practical to apply, because of the effect of the kind of future prognostication that is represented by these posts.

Using this lens, the two articles represent lists of what people desire the future to be. Fortunately, both are a bit more positive than Richard Watson’s chapter on the future from his forthcoming book Future Files: A History of the Next 50 Years, where he sees a future of depressing loneliness and disconnection. MacManus and his readers are much more positive, seeing a future where the web will deliver new systems to improve people’s lives. Simply by virtue of the fact that both versions of the future coexist right now, the new web that emerges will likely contain elements of both.

Posted by

John Jones

at

12:28 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: AI, cognitive science, cognitivism, connectionsim, Emergence, everyware, Internet, Mechanical Turk, semantic web

Wednesday, September 05, 2007

Speech-to-text using your cellphone

Read/Write Web has posted a review of Jott, a mobile phone service that allows users speech-to-text functions such as dictating email messages. They have just released a service called “Jott Links” (and an API) that allows users to interact with websites like Zillow and Twitter using voice commands and speech recognition.

Read/Write Web has posted a review of Jott, a mobile phone service that allows users speech-to-text functions such as dictating email messages. They have just released a service called “Jott Links” (and an API) that allows users to interact with websites like Zillow and Twitter using voice commands and speech recognition.

On the one hand this seems like a no-brainer, the perfect application of this technology. I spent a summer during college working for Speech Technology Magazine, and back then speech recognition software was mainly marketed for people with motor disabilities and those who liked to dictate their texts. With the proliferation of cell phones, it seems like this deployment of the technology should be a perfect fit for most people’s lifestyles. However, the limitations of the technology make me wonder how it will work. I could be hopelessly out of the loop here, but the speech recognition programs that I was familiar with back then depended on creating profiles of individual users, slowly learning how to decode the user’s speech through a trial-and-error process that required a lot of feedback in the form of corrections. Will Jott’s service do this, or has speech recognition evolved beyond this problem? If not, it could be a serious drawback. If a user wanted to post a message to a public service like Twitter, he or she will certainly want to make sure that message doesn’t contain any embarrassing malapropisms. It will be interesting to see if this feature catches on. There have been some significant developments in interface design lately, most notably the huge response that Apple has received for the iPhone and the iPod Touch, which was just released today. Perhaps they will coexist, and we will get used to an everyware-esque situation where our interactions with computing devices will fit much more naturally in our everyday actions.

It will be interesting to see if this feature catches on. There have been some significant developments in interface design lately, most notably the huge response that Apple has received for the iPhone and the iPod Touch, which was just released today. Perhaps they will coexist, and we will get used to an everyware-esque situation where our interactions with computing devices will fit much more naturally in our everyday actions.

Posted by

John Jones

at

11:46 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: everyware, interface, iPhone, iPod, iPod Touch, speech recognition, speech-to-text, ubicomp, Web 2.0