Last week, Adam Lee of SXTXState interviewed me and my fellow SXSW panelists about “Is Aristotle on Twitter?” Here’s the video:

The panel will be Tuesday, March 17 at 10:00 a.m. in room B. You can find more info here.

Last week, Adam Lee of SXTXState interviewed me and my fellow SXSW panelists about “Is Aristotle on Twitter?” Here’s the video:

Last summer I worked with Matt King, the CWRL’s resident video game expert, on the html for an article describing the current status of Rhetorical Peaks, a video game for teaching rhetoric and writing. The article has recently been published by CCC Online. Check it out.

Posted by

John Jones

at

10:06 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: pedagogy, Rhetoric, video games

In Free Culture: The Nature and Future of Creativity

, Lawrence Lessig argues that U.S. copyright laws have traditionally functioned to protect the freedom of culture to flourish. In its most common form before the previous century, copyright protected creators’ ability to control the publication—or its copying, not derivative uses—of their works for a limited period of time so as to ensure that there would be an incentive for the production of creative work. To ensure copyright, copyright holders had to mark their works with either the copyright symbol (©) or the word “copyright,” deposit a copy of the work with the government to ensure that it would remain available after the copyright term expired, and to either register the work with the government or renew the copyright if it was considered valuable enough to do so. Whatever works failed to comply with these provisions were considered part of the public domain and could be freely copied, distributed, or modified by anyone.

Copyright legislation in the twentieth century largely eliminated these provisions, however. Culminating with the Copyright Term Extension Act (CTEA), the U.S. government has continually increased the term of copyright such that very few cultural products have entered the public domain since the 1930s and completely eliminated the requirements that works be identified as being under copyright or registered with the government. Lessig attempts to show how these changes in copyright laws, coupled with the new behaviors for creating and disseminating creative materials brought about by new media technologies, have created a situation where the cultural capital of our society is increasingly controlled by the few elite individuals who have the power, resources, or inclination to navigate copyright regulations. According to Lessig, the basic structure of the internet makes practically all media usage “copying,” thereby making many kinds of usage that were previously out the range of copyright law—such as sharing mixtapes or clips of videos—now subject to it.

The most refreshing aspect of the book is that Lessig avoids the extremes of this debate: he is neither for blanket immunity from copyright restrictions nor restrictive legislation. He manages to avoid these extremes by not moralizing on copyright or taking only the damages that can be associated with copyright into account in his analysis. Rather, he focuses on copyright’s connection to the production and availability of cultural artifacts like music, movies, and books, arguing that while copyright legislation should punish uses that inhibit creativity—uses like downloading MP3s as a substitute for purchasing music—it shouldn’t limit the ability of culture to flourish through uses that don’t affect current copyright laws or which cause little damage to copyright holders. For example, he argues that VCRs were originally opposed by the movie and television industries because those industries assumed that the machine would hurt them financially. However, as VCRs became ubiquitous, it was discovered that their use promoted more sales of movies and television shows, and that copying off of television had very little economic impact on industry. Similarly, while Lessig argues against using P2P sharing to pirate music, he argues that the technology shouldn’t be crippled to avoid this problem because it can be used for other legal, culturally beneficial purposes.

As a rhetorician, I was interested in Lessig’s method in this book, particularly he examination of the ways in which “piracy” is defined in the copyright debate, as well as the history of the word’s usage to refer to practically any new media development that upset old ways of doing business. However, I was most interested in the middle section of the book where Lessig describes his fight in the Supreme Court to have CTEA declared unconstitutional. In this section, Lessig dwells for an extended period of time on the type of argument he made before the court—one that was overly logical, in his later opinion—versus the one he should have made. He claims that the reason he lost is that he failed to argue passionately to the court for why the CTEA caused damage to culture; instead he focused only on the constitutional issues involved in the case.

I found this section fascinating for a number of reasons. In the most general way, I was struck by how it demonstrated that even in what would presumably be an environment in which reason alone would determine the outcome of an attempt at persuasion—a Supreme Court case—, Lessig shows how the logos of his argument wasn’t enough to be convincing, and that he needed to include some pathos as well. More personally, I was able to empathize with his dejection after losing the case. I, too, have been in a situation where I realized belatedly that I had completely blown an argument by ignoring some simple, basic principle of rhetoric.

I also found this passage interesting for another reason: its complete lack of reference to the art of argumentation and persuasion. After his description of his argumentative failure, Lessig refers to rhetoric in the pejorative sense, equating it merely with style, flash without substance (p. 250). This passage only illustrated further how much rhetoricians have surrendered the public debate over argument and language to other disciplines.

In short, although the book is getting a bit old, Free Culture still seems fresh in its take on the copyright debate. I’m glad I finally got around to reading it.

Posted by

John Jones

at

2:27 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: Copyright, Culture, Lawrence Lessig, Review, Rhetoric

A while back, I posted a response to a panel I attended at the 2008 Computers and Writing Conference. The panel reported the work of a research group that was designing what amounts to a social network site based on writing. It is very rare to find someone in the field of rhetoric and writing who can program, and I thought it was a shame that this dedicated group of R&C programmers were trying to reinvent the social networking wheel. Generally, I think this situaiton is like the one Tim O’Reilly describes in this piece on the Yahoo-Microsoft merger.

I believe that we’re collectively working on an Internet Operating System, and that it will ultimately look more like Unix than it looks like Windows. That is, it will be an aggregate of best of breed tools produced by an army of independent actors, all playing by the same rules so that those tools work together to produce a whole greater than the sum of the parts.

Fighting over search is a bit like the Free Software Foundation re-implementing cat, ls, sort, and all the other Unix utilities that were already available in the Berkeley distributions of Unix. The real problem was solved by someone outside the FSF, when Linux Torvalds wrote a kernel, a missing piece that became the gravitational center of Linux, the center around which all of the other projects could coalesce, which made them more valuable not by competing with them but by completing them.

I don’t think writing researchers should be spending time rebuilding features that already exist elsewhere for free.

I should reiterate here that I think it is fantastic that writing researchers are coding websites and building web services. This is a crucial writing skill that I think we as a field have neglected in favor of sexier forms of writing like audio and video. However, what we should be programming are innovative new services that fit into the already existing Web 2.0 space, not building our own versions of existing (or new but more popular, better-supported) services.

So here’s a thought: if rhetoric and composition instructors want to use social networking apps, and they want to avoid sites like Facebook (when I voiced my objections after the panel discussion, one response was that sites like Facebook don’t offer the security necessary for protecting students’ work and grades), why don’t they find an unpopular social networking site and populate it? Here’s a list of social networking sites and their membership on Wikipedia. Instructors could find a largely defunct site, colonize it, and use their collective power to get the site to add features and functionality that fit the interests of the field? Of course, this would only work if many instructors and students from many different schools started using the site. However, it could be a great way to get free programming from a dedicated source while also taking advantage of features geared towards the needs of writing instructors.

Posted by

John Jones

at

7:30 PM

1 comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: CW 2008, programming, Rhetoric, social networking, Web 2.0, Writing

Lately I’ve been thinking about the problems that rhetoricians have sharing our knowledge with others outside the field. Ever since Ramus limited the scope of rhetoric to style and delivery, rhetoricians have been losing the public battle over the relevance of what we do. This situation was not much improved when rhetoric attached itself to freshman composition, the indentured servitude of academic disciplines. Like freshman comp, rhetoric is seen as somewhat remedial, unnecessary for people who are already good communicators.

Lately I’ve been thinking about the problems that rhetoricians have sharing our knowledge with others outside the field. Ever since Ramus limited the scope of rhetoric to style and delivery, rhetoricians have been losing the public battle over the relevance of what we do. This situation was not much improved when rhetoric attached itself to freshman composition, the indentured servitude of academic disciplines. Like freshman comp, rhetoric is seen as somewhat remedial, unnecessary for people who are already good communicators.

As a student of rhetoric, I find this view of rhetorical studies to be somewhat limiting, in that it ignores the substantial contributions that rhetoricians have made to our understanding of reading and writing practices, as well as of argument and other forms of communication.

Which brings me to this Lifehacker post which I saw over the weekend.

Job interview master Vj Vijai describes how make the best impression at a technical interview using people skills (versus technical skills). His talk, which happened at O'Reilly's awesome Ignite event, is informative, funny, and short. Vijai also has a web site outlining the principles.

I thought that description sounded catchy, so I clicked on the link and here’s what I saw:

NLP or Neuro-Linguistic Programming is a rogue branch of pschylogy that is based on the premise that language and communication can be used to influence people.

What he is teaching isn’t hacking or psychology but rhetoric! This conclusion is reinforced by reading the comments on the Lifehacker post. They read like a greatest hits of criticism of rhetoric: if this is so great, why doesn’t it work all the time? Isn’t this manipulation?

I am continually shocked that rhetoricians have allowed our subject matter to be hijacked in this way, but I‘m not sure how we can reenter the conversation without seeming out of touch—quick, which term is more appealing, ‘pathos’ or ‘Jedi mind tricks’?—or worse, whiny.

Anyway, here’s the video of Vijai’s talk:

CNET’s Caroline McCarthy has posted a summary of one of Lawrence Lessig’s speeches associated with his Change Congress initiative.

CNET’s Caroline McCarthy has posted a summary of one of Lawrence Lessig’s speeches associated with his Change Congress initiative.

“Even though today the individuals [in Congress] are better than the individuals who populated our government in the past, the problem of this corruption is much worse,” Lessig explained. “And it’s much worse because government today is much more significant. It’s first more critical to core national problems...and second, it’s more pervasive. The government’s fingers are everywhere.”

...

But the other big difference between the 19th century’s politics and today’s is what’s making possible Lessig’s mission at Change Congress: Daniel Webster’s America didn't have Wikipedia, WordPress, or Twitter. (It would’ve been kind of cool, though: “Wig shopping with @henryclay, then out to eat. WTF is with these tea prices?”) The Web’s tools have made it possible for far more information to make it into the hands of ordinary citizens, and those citizens in turn can use the Web to band together and work toward democratic action.

The post made me think of George Lakoff’s new book The Political Mind. According to Amazon, the book seems to be a rhetorical look at politics over the last decade or so, focusing on the ways in which pure rationality has failed progressives. I bought a copy yesterday, and I’m excited about reading it.

Posted by

John Jones

at

11:17 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: Lawrence Lessig, politics, Rhetoric

From Figaro:

The rumpled crusader maintains that that his campaign shouldn’t affect the outcome at all. But it’ll jack up his ego like a pimped-out Corvair.

Figaro interviewed Nader in 2000, months before he denied Democrats a win in the crucial Florida balloting. When Figaro asked if someone put a gun to his head and told him to vote for either Gore or Bush, which he would choose, Nader answered without hesitation: “Bush.” Al Gore, he said, had “totally betrayed” his environmental stand. “If you want the parties to diverge from one another,” Nader continued, “have Bush win.”

Mission accomplished.

AcademHacK David Parry has an editorial in Science Progress responding to educational institutions banning Wikipedia. He argues that outlawing sites like Wikipedia robs students of much-needed training in using new media.

we do a fundamental disservice to our students if we continue to propagate old methods of knowledge creation and archivization without also teaching them how these structures are changing, and, more importantly, how they will relate to knowledge creation and dissemination in a fundamentally different way.

I particularly enjoyed Parry’s description of the encyclopedia:

No longer is an encyclopedia a static collection of facts and figures (although some of its features might be relatively so); it is an organic entity. To educational and policy institutions which, for a substantial portion of history, have maintained control over static codex centered archives—think not only academic libraries, but national ones as well—the shift to an organic structure which they no longer control or solely influence represents a crisis indeed. But to train students in old literacy seems to me to be fundamentally the wrong approach. As Howard Rheingold suggests in Smart Mobs, in the future individuals will be divided between “those who know how to use new media to band together [and] those who don’t.”

While Parry might be giving “educational and policy institutions” short shrift [subscription needed], I think he is exactly right about encyclopedias. In fact, when I talk with people about Wikipedia, I like to go further and argue that the encyclopedia—the “static collection of facts and figures” Parry describes, which, I would argue, is held by many to be an objective repository of unassailable knowledge—has never existed, and never could exist.

Despite the protestations to the contrary of some encyclopedia creators, the encyclopedia has never been a repository of objective knowledge but is and always has been a situated cultural artifact that can only be reliably counted on to record what counts as knowledge at a particular moment in history. Subsequently, encyclopedias are as prone to error and crimes of omission as any other text, and criticizing Wikipedia for not being a “proper” encyclopedia—again, a thing that has never existed—is a bit like criticizing a horse for not being a unicorn.

That’s why I think Parry’s description of Wikipedia as an “organic” body of knowledge is a much more workable, accurate definition of the encyclopedia than the received definition. While Wikipedia does represent a shift in what counts as knowledge and how that knowledge is to be archived and accessed, the fact of the matter is that the encyclopedia has always been a shifting, living thing; with Wikipedia the technology has caught up to the reality.

There is a downside to this new approach to the encyclopedia, though. Wikipedia is not merely a living, organic body of knowledge, but it is also a democratized body of knowledge. As Parry notes, Wikipedia doesn’t merely provide the settled opinion on a subject, but it also provides “debate and discourse around” that subject. In the case of heavily debated topics like global warming and evolution, that preference for debate has given non-scientific voices a prominence they probably don’t deserve, making it seem that debate exists where it perhaps does not. However, I believe this democratization—where debate is open to the public—is preferable to the old hierarchy, where the authority of publishing is the final arbiter of which knowledge is approved and which is not, for it lends prominence to the rhetorical positioning of knowledge, making rhetorical tools much more important for those who would have their ideas accepted in the commons.

This problem only lends more support to Parry’s argument: that students need to be familiar with this new approach to knowledge ushered in by new media, and scientists and other knowledge workers “will need to posses a new type of collaborative literacy”—one steeped in rhetoric and the techniques for gaining adherence to ideas—in order to disseminate their findings.

Posted by

John Jones

at

10:20 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: information, knowledge, New Media, Rhetoric, Wikipedia

Jonah Weiner has a new piece in Slate bashing Wes Anderson for, among other things, his depiction of non-white characters in his films. Weiner’s argument centers primarily on Anderson’s new movie, The Darjeeling Limited, which is set in India (and which I have not seen). While the argument is largely compelling, one of Weiner’s claims so misrepresents a scene from The Royal Tenenbaums that it damages the whole. Here’s the quote:

Anderson generally likes to decorate his margins with nonwhite, virtually mute characters: Pelé in Life Aquatic, a Brazilian who sits in a crow’s-nest and sings David Bowie songs in Portuguese; Mr. Sherman in Royal Tenenbaums, a black accountant who wears bow ties, falls into holes, and meekly endures Gene Hackman’s racist jabs—he calls him “Coltrane” and “old black buck,” which Anderson plays for laughs; Mr. Littlejeans in Rushmore, the Indian groundskeeper who occasionally mumbles comical malapropisms (Anderson hired this actor, Kumar Pallana, to do the same in Royal Tenenbaums and Bottle Rocket). There’s also Margaret Yang, Apple Jack, Ogata, and Vikram. Taken together, they form a fleet of quasi-caricatures and walking punch lines, meant to import a whimsical, ambient multiculturalism into the films.

While in aggregate I think Weiner has a point, I think his summation of the scene between Danny Glover’s Henry Sherman and Gene Hackman’s Royal Tenenbaum is tremendously misleading. Here’s the scene that Weiner is referring to:

I think it is really difficult to describe Glover’s reaction to Tenenbaum’s racial taunts as “meek endurance.” On the contrary, the scene explodes into a furious shouting match, and, unlike Weiner’s claim that all Anderson’s non-white characters are “virtually mute”—with the implication being that they are one-dimensional caricatures—Glover’s dialogue is succinct and his performance in the scene is extremely nuanced.

I understand the impulse that led Weiner to overstate his case here: once you have created a theory, it is easy to assume that that theory is totalizing and to try to apply it to all situations. This is a problem faced by everyone who has ever tried to create an argument. However, I think the Glover example suggests the difficulties in trying to be this totalizing. A more nuanced argument would account for this apparent aberration—I would suggest that it might have something to do with Glover’s status as a professional actor, a status that is not held by many of the performers who played the roles of the offensive characters Weiner lists—or possibly scrap the argument in favor of one that could account for this scene.

Posted by

John Jones

at

11:50 AM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: research, Rhetoric, Slate, Writing process

Update: This post is a partial review of Malcolm Gladwell’s Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking. A key question in rhetoric and communication studies is how people are persuaded to act. Sometimes the act in question is overt in that it is the completion of some action; other times, the action could be implicit, in that it is the acceptance of some idea or line of reasoning as being true (or false). This latter group of actions are variously referred to as decisions or making up one’s mind. (I don’t consider these categories to be all that rigid. Consider them convenient shorthand for some temporary ideas—an argumentative place to hang your hat.) In Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking (2005), Malcolm Gladwell argues that many of our decisions are made without our conscious input, that they are the result of unconscious processes that occur independently of our considered, conscious thought.

A key question in rhetoric and communication studies is how people are persuaded to act. Sometimes the act in question is overt in that it is the completion of some action; other times, the action could be implicit, in that it is the acceptance of some idea or line of reasoning as being true (or false). This latter group of actions are variously referred to as decisions or making up one’s mind. (I don’t consider these categories to be all that rigid. Consider them convenient shorthand for some temporary ideas—an argumentative place to hang your hat.) In Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking (2005), Malcolm Gladwell argues that many of our decisions are made without our conscious input, that they are the result of unconscious processes that occur independently of our considered, conscious thought.

Many of Galdwell’s proofs for this idea come from the ideas of complexity theory and have interesting applications to rhetoric. In the first case, Gladwell references Paul Ekman and W. V. Friesen’s Facial Action Coding System (FACS) (here is a link to a brief explanation of FACS, and a FACS chart is pictured below). Ekman and Friesen documented over 10,000 configurations of the facial muscles, of which they found about 3,000 that were meaningful. This result comes from the layering of actions in the facial muscles, actions which grow exponentially as more muscles are worked together (or in sequence). The result seems very much like a strange-attractor type problem, where out of many countless meaningless results—what Gladwell calls ‘the kind of nonsense faces that children make’ (201)—a few stable meaningful results arise.

In Gladwell’s discussion of ‘thin-slicing’, his name for the ability to find emergent (my word, not his) properties of a system in very small samples of that system—say, ten seconds of a couple’s conversation is sufficient to make a highly-probably determination of that couple’s future, or a similarly small sample of Morse code is enough for a trained listener to be able to identify the operator transmitting that code. According to Galdwell, this code pattern from the second example, called a fist, ‘reveals itself in even the smallest sample of Morse code’ and ‘doesn’t change or disappear for stretches or show up only in certain words or phrases’ (29). This fact would seem to indicate that the fist is not irreducibly complex, that is, that the message is not the shortest possible way of describing the fist, for the fist shows up even in very small samples of the message.

In complexity theory, the irreducibly complex is equivalent to the random. Take the example of a random string of numbers. This string is the prototype of an irreducibly complex message because it cannot be expressed in a reduced form. The shortest method of reproducing a string of random numbers is the string itself. Language theorists like Jacques Derrida seem to argue that all symbol messages are irreducibly complex in this way, that they cannot be expressed in any shorter form than what they are, for to shorten or summarize them would be to make a different message by leaving out key information.

The fist example seems to indicate, however, that some significant portion of symbol messages, those parts that are roughly equivalent to style, are able to be reduced and maintain their identity. I’m not quite sure what the implication of this result is, but I find it interesting, especially in the context of analog and digital communication. Though Morse code is essentially a digital medium, the fist only appears as an analog aftereffect of the digital message. Similarly, Nicholson Baker’s advocation for the preservation of library card catalogs is an example of a digital message that is willing to discard analog aftereffects that are deemed unimportant.

Now, it is obvious that the digital portion of a message is also not irreducibly complex. New methods of compression might make it possible to transit the same message in a shorter form. The counterpart in communication theory, I suppose (and someone feel free to correct me if I’m getting all of these theories in a muddle), is that the iterable nature of symbol systems allows for shorthand communication of messages.

If messages are made up of both digital and analog components, neither of which are, by themselves, irreducibly complex, what then, in the Derridian sense, is the irreducible part of the message? I wonder if it is the interplay between these two elements, the connection between the analog and the digital, that is random and irreducible.

One of Gladwell’s arguments in Blink is that it is in our interest to discover where our unconscious decisions arise from as a means of determining whether or not they are to be trusted. On that note, a final thought: the analog portion of the message is much more difficult to counterfeit than the digital, though such imitation is not impossible. When all information is digitized, it is able to be copied—falsified—endlessly, much more easily than analog messages. This is because digital messages lack the global, emergent features of the reducibly complex, like the Morse code operator’s fist. As digital information is still carried via analog devices (analog telephone lines, for instance) it is possible that this portion of the signal can be analyzed for identifying features. One solution to our current concerns with digital security might be finding a way to reconnect the analog and the digital, making individual messages more difficult (perhaps impossible?) to counterfeit.

Posted by

John Jones

at

2:56 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: Communication, Complexity, Emergence, Review, Rhetoric

Update: This post is a partial review of Edward Tufte’s Visual Explanations: Images and Quantities, Evidence and Narrative. Edward R. Tufte describes a confection as a group of visual elements assembled to describe or enhance a written argument in his 1997 bookVisual Explanations. A confection, he argues, is distinct from both collages, which are intended to convey messages not associated with written arguments, and diagrams, which convey messages but whose elements lack the disparate nature of a confection. A straightforward photograph is, according to Tufte, not a confection; but two photographic images superimposed upon one another to create a fantastical mélange that cannot be photographed would be a confection. In this sense, a confection is an arrangement of disparate elements so as to make an argument. (One example is the title page of Hobbes’s Leviathan, pictured below.) It is this arrangement, the confection’s fantastical placement—either in space or in time—of otherwise unrelated visual elements, that makes them theoretically interesting.

Edward R. Tufte describes a confection as a group of visual elements assembled to describe or enhance a written argument in his 1997 bookVisual Explanations. A confection, he argues, is distinct from both collages, which are intended to convey messages not associated with written arguments, and diagrams, which convey messages but whose elements lack the disparate nature of a confection. A straightforward photograph is, according to Tufte, not a confection; but two photographic images superimposed upon one another to create a fantastical mélange that cannot be photographed would be a confection. In this sense, a confection is an arrangement of disparate elements so as to make an argument. (One example is the title page of Hobbes’s Leviathan, pictured below.) It is this arrangement, the confection’s fantastical placement—either in space or in time—of otherwise unrelated visual elements, that makes them theoretically interesting.

Let me explain why. Accepting the above definition, I ask: what does it mean to say that a confection makes—either implicitly or explicitly—an argument? That is, is the argument made by the confection independent of its fantastical arrangement, or is the argument dependent on this arrangement?

I’m thinking two things: 1) since the characteristic of confections that makes them so—the arrangement of disparate elements to make an argument—is true of all graphical arguments, be they diagrams, graphs, straight photographs, and drawings, does it not also follow that all graphical output is confectionary in some degree? And doesn’t this realization of the fantastical in all graphics lead to certain conclusions about their trustworthiness and veracity? More on this after: 2) Isn’t the very construction of a causal argument confectionary in its selection and arrangement of elements that are not adjacent in space and time?

This, I think is a key point, for what makes a graphic a confection makes it an argument. Realizing this fact—that what argues is confectionary—provides a graphical explanation that undermines claims of objectivity or absolutism on the parts of even the most clever conclusions.

Update: This post is a partial review of John Holland’s Hidden Order: How Adaptation Builds Complexity and Mitchel Resnick’s Turtles, Termites, and Traffic Jams: Explorations in Massively Parallel Microworlds.

Both John Holland (Hidden Order, 1995) and Mitchel Resnick (Turtles, Termites, and Traffic Jams, 1994) argue that it is difficult to discern the behavior of a system from the behavior of its parts. Through the use of computer modeling—cellular automata in Holland’s case, the StarLogo programming environment in Resnick’s—both attempt to begin to understand the nature of these complex systems. Holland defines complex systems as a product of “the interactions” between their relatively simple parts (3). The result of these interactions, which are often relatively simple themselves, is that the “aggregate behavior of a diverse array of agents”, or the “parts” of the system, “is much more than the sum of the individual actions” of those parts (31). That is, the ordered behavior comes as a result of the particular way in which objects interact, rather than from any kind of centralized oversight, which is presumed to be the source of most ordered behavior. Holland gives the example of a city as a complex system that “retain[s]” its “coherence despite continual disruptions and a lack of central planning” (1). Now most cities obviously have central planning architectures in the form of governments, but those centralized authorities often find it their job to combat or enforce city behavior that does not originate directly (at least in appearance) from their decisions. Where do city-level features like traffic jams, ethnically- or economically-segregated neighborhoods, and homelessness come from? Rarely can they be directly attributed to central planning. Rather, the interactions between residents—which are often dictated by central planning organizations—and other structures in the environment help to form and maintain the city and its “personality.” This aggregate behavior results in “an emergent identity” that, though continuously changing, is remarkably stable (3).

Holland defines complex systems as a product of “the interactions” between their relatively simple parts (3). The result of these interactions, which are often relatively simple themselves, is that the “aggregate behavior of a diverse array of agents”, or the “parts” of the system, “is much more than the sum of the individual actions” of those parts (31). That is, the ordered behavior comes as a result of the particular way in which objects interact, rather than from any kind of centralized oversight, which is presumed to be the source of most ordered behavior. Holland gives the example of a city as a complex system that “retain[s]” its “coherence despite continual disruptions and a lack of central planning” (1). Now most cities obviously have central planning architectures in the form of governments, but those centralized authorities often find it their job to combat or enforce city behavior that does not originate directly (at least in appearance) from their decisions. Where do city-level features like traffic jams, ethnically- or economically-segregated neighborhoods, and homelessness come from? Rarely can they be directly attributed to central planning. Rather, the interactions between residents—which are often dictated by central planning organizations—and other structures in the environment help to form and maintain the city and its “personality.” This aggregate behavior results in “an emergent identity” that, though continuously changing, is remarkably stable (3). Similarly, Resnick explicitly focuses on these “decentralized interactions” and the systems that result from them (13). He provides five “Guiding Heuristics for Decentralized Thinking”: 1) “Positive Feedback Isn’t Always Negative”, that is some kinds of positive feedback, in the economy for instance, can lead to increases, rather than decreases, in order; 2) “Randomness Can Help Create Order”; 3) “A Flock Isn’t a Big Bird”—systems do not behave like a larger version of their components; 4) “A Traffic Jam Isn’t Just a Collection of Cars”, or decentralized systems are more than the sum of their parts; and finally 5) “The Hills Are Alive”—the environment and context of a decentralized system are key components of its behavior (134).

Similarly, Resnick explicitly focuses on these “decentralized interactions” and the systems that result from them (13). He provides five “Guiding Heuristics for Decentralized Thinking”: 1) “Positive Feedback Isn’t Always Negative”, that is some kinds of positive feedback, in the economy for instance, can lead to increases, rather than decreases, in order; 2) “Randomness Can Help Create Order”; 3) “A Flock Isn’t a Big Bird”—systems do not behave like a larger version of their components; 4) “A Traffic Jam Isn’t Just a Collection of Cars”, or decentralized systems are more than the sum of their parts; and finally 5) “The Hills Are Alive”—the environment and context of a decentralized system are key components of its behavior (134).

Resnick sees the decentered view of the world as necessary to changing deeply-entrenched centralized ways of thinking. According to him, this decentered view became apparent in the work of Freud and his description of the unconscious, and other decentered metaphors have been slowly gaining ground in other fields since then.

This view of the world as being primarily the product of decentered behavior has interesting applications for rhetoric, for persuasive situations are as decentered and interaction-dependent as the systems studied by Resnick and Holland. Resnick notes that as decentered thinking—in the form of chaos and complexity theory—has gained traction, “scientists have shifted metaphors, viewing things less as clocklike mechanisms and more as complex ecosystems” (13). Rhetoricians since the sophists, however, have known the complex, dependent nature of communication, where “decentralized interactions” like the complex interactions of rhetorical appeals and “feedback loops” of self- and community-reinforcement (13) are well known.

These connections imply that rhetoric is well-suited for application of decentralized thinking. Certainly there is a tendency even in rhetoric to over-emphasize centralized behaviors to the detriment of decentralized ones—see the work of Peter Ramus. As rhetoric continues to move closer to a sophistic understanding of the power of persuasion, the models of Resnick and Holland have the possibility of shedding light on rhetorical situations, providing a language to explain behaviors that, though recognized, might have been previously unexplainable.

Posted by

John Jones

at

5:49 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: cellular automata (CA), chaos, Complexity, Emergence, Review, Rhetoric

Update: This post is a partial review of Kenneth Boulding’s Ecodynamics and James Gleick’s Chaos: Making a New Science

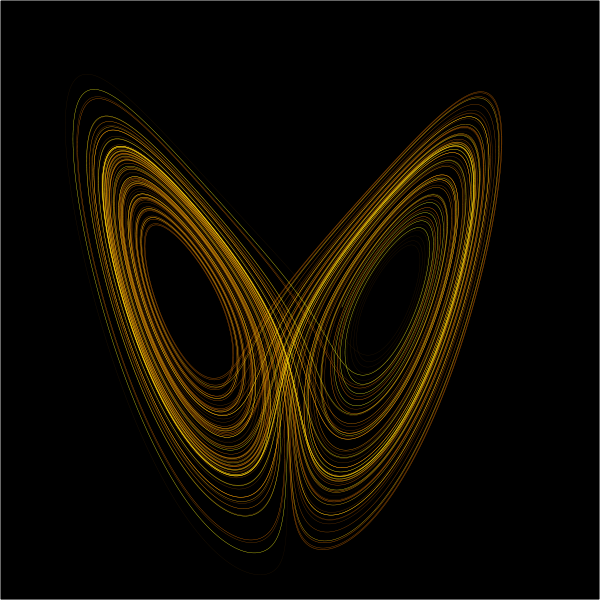

Lately I’ve been thinking a lot about the metaphors that Kenneth Boulding uses to describe the natural world in his Ecodynamics (1978). One such metaphor is evident in his statement that knowledge, or know-how, is embedded in the structure of natural objects. The way in which Boulding expresses this idea is that “in a certain sense, helium ‘knows how’ to have two electrons and hydrogen knows only how to have one” (14). This is a case where ‘structure’ has the ‘ability to “instruct”’ (13). One benefit of this particular way of looking at knowledge is that it limits what is determined about a subject to what can be known. A fact of an atom of helium is that it is an atom of helium, and that fact can be stated in terms of know-how. (Boulding uses this method to show how unhelpful the idea of the survival of the fittest is, for it really is just a statement about the survival of the survivors.) This metaphor is particularly powerful because it allows for our understanding of communication to explain natural phenomena like the replication of DNA. Know-how is communicated from the existing structure through other materials that lend themselves to communicating that structure as well. By accepting this metaphor, statements about language, the realization that “communication . . . becomes a process of complex mutuality and feedback among numbers of individuals that leads to the development of organizations, institutions, and other social structures which affect” the outside world (16). The spread of know-how through communication—the “multiplication of information structures” (101)—leads to complex behavior and organization, in persons as well as in nature. This phenomenon, communication through the propagation of order and know-how, can be seen in other natural structures. In Chaos: Making a New Science (1987), James Gleick identifies several of these phenomena like entrainment or modelocking, an example of which being when several pendulums, connected by a medium like a wooden stand that can communicate relevant information like rhythms, all swing at the same rate (293). Similarly, in the phenomena of turbulence, “each particle does not move independently”; in their interdependent interaction, the motion of each “depends very much on the motion of its neighbors” (124). I don’t think that it is much of a stretch to say that know-how is propagated through the constraints of strange attractors (the image to the left is of the Lorenz attractor) and similar phenomena. Chaotic phenomena behaves in a particular way because that is what it knows how to do.

This phenomenon, communication through the propagation of order and know-how, can be seen in other natural structures. In Chaos: Making a New Science (1987), James Gleick identifies several of these phenomena like entrainment or modelocking, an example of which being when several pendulums, connected by a medium like a wooden stand that can communicate relevant information like rhythms, all swing at the same rate (293). Similarly, in the phenomena of turbulence, “each particle does not move independently”; in their interdependent interaction, the motion of each “depends very much on the motion of its neighbors” (124). I don’t think that it is much of a stretch to say that know-how is propagated through the constraints of strange attractors (the image to the left is of the Lorenz attractor) and similar phenomena. Chaotic phenomena behaves in a particular way because that is what it knows how to do.

Supposing we can accept this metaphor for behavior in nature, that it is a kind of communication where what is being communicated is knowledge, then it seems like it would be completely reasonable to use the language of rhetoric to describe natural behavior. The sensitive interdependence of the parts of a system, recognized 1) by Boulding in animal development where “the history of a cell in an embryo depends on its position relative to others rather than its past history, because its position determines the messages”—or information—“that it gets” (107), and 2) by the physicist Doyne Farmer, who, in describing mathematical equations notes “the evolution of [a variable] must be influenced by whatever other variables it’s interacting with,” for “their values must somehow be contained in the history of that” variable (266) suggests a rhetorical way of looking at nature. As Boulding acknowledges, everything depends on everything else, a point that rhetoricians have been making about the persuasive situation since the discipline was formed. This connection opens up the exciting possibility of rhetorical analysis of natural systems, where the tools of monitoring persuasion in language could be used to track the movement of know-how through nature.

Posted by

John Jones

at

10:02 PM

0

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: attractors, chaos, Communication, Complexity, information, know-how, Review, Rhetoric

Update: This post is a partial review of Gregory Bateson’s Steps to an Ecology of Mind In his references to communication, Bateson provides an intriguing alternative to the prevailing model of the persuasive process. That process is largely considered to consist of an author/speaker presenting some superior content, and that content, through its effective presentation, persuading an audience of the author’s thesis. (This is certainly not the only model for communication, but I would think it is the one that most people—especially non-academics—would adhere to.) Rhetoricians would focus on the importance of the presentation, that is, all of the choices the author/speaker makes in presenting the content, but primacy would be given to the content. This formulation privileging content would not only be considered the best one, but possibly the most ethical one as well.

In his references to communication, Bateson provides an intriguing alternative to the prevailing model of the persuasive process. That process is largely considered to consist of an author/speaker presenting some superior content, and that content, through its effective presentation, persuading an audience of the author’s thesis. (This is certainly not the only model for communication, but I would think it is the one that most people—especially non-academics—would adhere to.) Rhetoricians would focus on the importance of the presentation, that is, all of the choices the author/speaker makes in presenting the content, but primacy would be given to the content. This formulation privileging content would not only be considered the best one, but possibly the most ethical one as well.

Bateson presents an alternative. Although he does not ignore the importance of content, his model of communication focuses on the presentation, what he refers to variously as “structure” or “patterns,” of that communication, rather than what is being presented, and these structures carry information about relationships. Referring to his own speech at an academic conference, Bateson remarks that his real topic “is a discussion of the patterns of [his] relationship” to the audience, even though, as he tells them, that discussion takes the form of his trying to “convince you, try to get you to see things my way, try to earn your respect, try to indicate my respect for you, challenge you” (372). In other words, the acceptance of the content is dependent upon how well he as a speaker is able to affirm that relationship. In another example, he points out that if one were to make a comment about the rain to another person, hearer would be inclined to look out the window to verify the statement. Though he notes that such behavior can seem confusing because it is redundant, this redundancy is not a question of the first speaker’s truthfulness, but rather an example of an attempt to “to test or verify the correctness of our view of our relationship to others” (132).

This patterning or structure, the need to comment on the relationship between speaker an audience by 1) conforming to arbitrary rules (another kind of structure) like those set up in an academic conference or 2) reminding ourselves that a person is a trustworthy source of information, is, to Bateson, representative of “the necessarily hierarchic structure of all communicational systems” which manifests itself in communication about communication (132). For Bateson, this realization has at least two outcomes. First, in learning it means that what is learned by the subject is often not the topic under study per se, but how “the subject is learning to orient himself to certain types of contexts, or is acquiring ‘insight’ into the contexts of problem solving,” that is, “acquir[ing] a habit of looking for contexts and sequences of one type rather than another, a habit of ‘punctuating’ the stream of events to give repetitions of a certain type a meaningful sequence” (166). Second, this means that these structures of “contexts and sequences” replicate themselves in learners, who then become audiences, and those audiences respond to recognition (perhaps the wrong word) of that structure. As Bateson says, “in all communication, there must be a relevance between the contextual structure of the message and some structuring of the recipient” for “people will respond most energetically when the context is structured to appeal to their habitual patterns of reaction” (154, 104). In these situations, what appeals to or persuades the audience is not the content, but the recognition of the familiar structure in the communication in question.

I think this focus on the structure of communication and the way in which that structure replicates itself across individuals highlights the technological dimension of speech—the way in which “meaning” is dependent upon the form of language—and has some interesting applications for the question of ethics and truthfulness in rhetoric, a topic I will comment on in my next post.

Posted by

John Jones

at

9:22 PM

3

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: Communication, Complexity, Cybernetics, Emergence, Review, Rhetoric

Update: This post is a partial review of Gregory Bateson’s Steps to an Ecology of Mind Reading Gregory Bateson’s introduction to his Steps to an Ecology of Mind, two things jumped out at me. First was his notion that human processes had to that point (1971) been described in terms of energy, a tendency which Bateson points out is misleading, for it frames the discussion of human cognitive processes—“behavior”—in terms of “mass and length” (xxix). Instead, Bateson suggests that these processes should be looked at in regards to a completely different paradigm: that of ordering. Bateson calls the energy example “the wrong half of the ancient dichotomy between form and substance” (his point illustrated with two accounts of creation, both of which are focused on this division) (xxxii).

Reading Gregory Bateson’s introduction to his Steps to an Ecology of Mind, two things jumped out at me. First was his notion that human processes had to that point (1971) been described in terms of energy, a tendency which Bateson points out is misleading, for it frames the discussion of human cognitive processes—“behavior”—in terms of “mass and length” (xxix). Instead, Bateson suggests that these processes should be looked at in regards to a completely different paradigm: that of ordering. Bateson calls the energy example “the wrong half of the ancient dichotomy between form and substance” (his point illustrated with two accounts of creation, both of which are focused on this division) (xxxii).

The form-substance dichotomy has interesting parallels with language theory, particularly in the flawed notion that substance is superior to form; in language, this distinction might be made between, speaking loosely, grammar and meaning. While substance/meaning is of great importance—in science as well as language—one cannot understand it apart from form. I was particularly interested in this point because this kind of investigation can take the form of a “rhetoric.”

I will explain with my second point of interest: this connection between form-substance and the practice of rhetoric (which I feel is significant, though I realize my statement of this significance is loose as of yet) seemed to be emphasized early in Bateson's introduction. He writes “But the definition of an ‘idea’ which the essays [in this book] combine to propose is much wider and more formal than is conventional. . . . let me state my belief that such matters as the bilateral symmetry of an animal, the patterned arrangement of leaves in a plant, the escalation of an armaments race, the processes of courtship, the nature of play, the grammar of a sentence, the mystery of biological evolution, and the contemporary crises in man's relationship to his environment, can only be understood in terms of such an ecology of ideas as I propose” (xxiii). Earlier he explains that the “ecology of ideas” he refers to is connected to what he calls minds. In the case of this long quote, I think there is an intimate relationship between many of the things listed (courtship, play, arms races, grammar) and what is known as rhetoric. Any one of the items I have just listed could be discussed in terms of “The Rhetoric of X” in the sense that Bateson is getting at. It is my feeling that he is attempting to ask fundamental questions about order that are related to the kinds of answers that rhetoric has tried to use to explain complex human interactions like persuasion. Certainly the part of “rhetoric of” that fails is when one focuses only on rhetoric textbooks, that is mere instructions of how to do something, but Bateson here opens the door (I think) to a conversation between rhetoric and his ecologies.

Bateson’s chapter “Experiments in Thinking About Observed Ethnological Material” in particular seems like nothing more than a rhetoric of scientific discovery, where he proposes that in science there should be alternate periods of “loose thinking and the building up of a structure on unsound foundations” followed by “the correction to stricter thinking and the substitution of a new underpinning beneath the already constructed mass” (86). One way in which this kind of see-sawing method can be achieved is through “train[ing] scientists to look among the older sciences for wild analogies to their own material” (87). Also interesting (I'll try and return to it later) is his worry that in some stages of his career he relied too heavily on words that were “too short and therefore appear more concrete than they are,” which seems to be a specific case of dissonance between form and substance (82).

Posted by

John Jones

at

9:42 PM

2

comments

![]()

![]()

Tags: Complexity, Cybernetics, Emergence, Review, Rhetoric